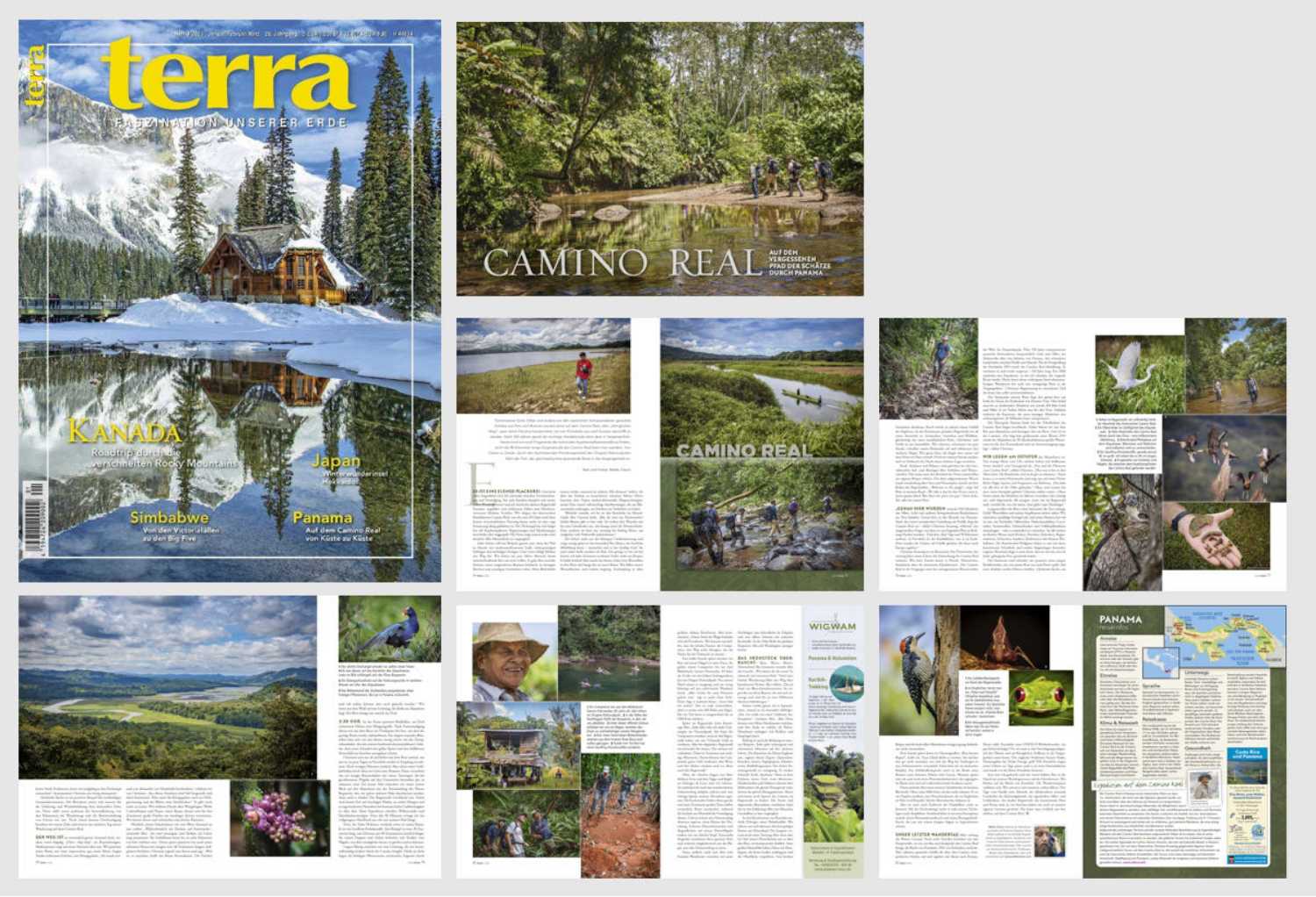

Published in:

Germany’s biggest nature travel magazine

12 pages | text & photographs

It’s a miserable slog. And worth every moment! My thoughts oscillate between imprecation and ecstasy. For eight hours, my seven hiking companions and I have been fighting our way through Panama’s dense rainforest, led by the experienced guide and machete virtuoso Molinar Torribio.

We are following the historic Camino Real trade route, of which little more than a vague memory remains, some 165 years after its last commercial use. The jungle has long since absorbed or washed away almost all the cobblestones, boundaries and markings. Perhaps this is nature’s way of showing us: Everything human is transient.

The path is littered with insect-eaten leaves

Every step is taken with care. The path is littered with insect-eaten leaves, unruly snares and prickly branches. At the very front, Molinar clears the way. We keep a few metres away to avoid being missed by the rebounding branches.

Then I continue over rotten trunks, under fallen trees, past thorny bushes and nettles. My gaze lingers in wonder at the armies of mushrooms that seem to be marching over dead wood. My ears follow the chirping of buzzing flycatchers, my nose smells the sweet, musty vapours that rise from the lush, radiant inflorescences to lure insects to their doom.

We walk the Camino Real in Panama for well over eight hours a day – through ankle-deep mud, up and down steep hills, through paths cleared with machetes and knee-deep rivers – which places the highest demands on footwear and clothing. On the physique anyway.

And now my hiking boots are sinking into the mud up to my ankles. Guide Alex Guevara laughs: “Are you a flat-rooter? There are lots of trees like that here. They only drive their roots down to the clay soil, i.e. just below the layer of mud. There they grow wide, twenty to fifty metres, in order to absorb as many nutrients as possible.”

I free myself from the loamy grip and a little later climb into the knee-deep Río Mauro, which rewards me with a marvellous cool-down. After all, it’s thirty degrees. We stop for a rest near a pump. I jump in as I am, I don’t have a dry thread left on my body anyway. It’s wonderfully cool! Alex dips the blue ten-litre water filter into the river and hangs it on a tree. We fill our water bottles and drink eagerly.

But we have to make good time and reach our next camp before nightfall

Exhaustion is evident on all our faces. It quickly gives way to euphoria, to the fascination of the primary rainforest, which sweeps into us with all its intensity of noise, wetness and wildness and at the same time with inexplicable calm, equanimity and grandeur. We joke around, munch on a few snacks, strap on our rucksacks and climb the next hill. How I would have loved to stay down there on the rock in the river. But we have to make good time and reach our next camp before nightfall.

The inflorescence of the Eschweilera jacquelyniae, a woody plant species that only occurs in Panama and is threatened by habitat loss.

Strength, stamina and balance are required for the constant ascents and descents over hills and watersheds. Here you can experience the cycle of nature directly on your own body: The water you have just absorbed drips down your forehead and the tip of your nose back onto the rainforest floor for hours.

“Welcome to the jungle”, sings Axl Rose in my head, “We take it day by day. If you want it, you’re gonna bleed. But that’s the price you pay.” That’s right, Axl, everything has its price.

It was here, that the Camino Real began

Forgotten path in the green

“This is where mules were first loaded with silver bars, gold and other conquistador treasures from Peru in 1519. It was here, in the old town of Panama City, the first European foundation on the Pacific, that the Camino Real began,” explains Christian Strassnig as his outstretched finger wanders northwards from the square in front of us, “and there, five days and ninety kilometres away, in Portobelo on the Caribbean coast, it came to an end. There the treasures were reloaded onto ships that then sailed to Europe.”

Rare in the rainforest: a completely intact section of the historic Camino Real.

Christian Strassnig is an obsessive. An Austrian who has dedicated twenty years of his life to researching the Camino Real. He knows the details, history and anecdotes about the historic trade route like no other: “The Camino Real is a predecessor of the Panama Canal, one of the most utilised waterways in the world. For more than 350 years, Spanish colonists mainly transported gold and silver from South America across the isthmus, the narrowest strip of land between the Pacific and the Atlantic.

With the completion of the railway in 1855, the Camino Real became superfluous. It became overgrown and was forgotten. For 150 years. It was not until 2008 that an expedition I took part in rediscovered the original route. Today, this hidden gem offers adventurous hikers like you a unique journey into the past.” Christian’s enthusiasm is infectious. And should prove to be true.

Soldiers secured the caravan, which had a current market value of around 30 million euros

The starting point of our journey is right here, at the foot of the tower of Panama Viejo Cathedral. Up to three hundred mules were loaded here with 100kg of gold and silver each. Drivers led two to three animals. Soldiers secured the caravan, which had a current market value of around 30 million euros.

Urban Panama City has long since swallowed up the remains of the Camino Real. So we take the bus to Lake Alajuela and board a boat there. And where is the Camino? “It’s mostly under water here. Lake Alajuela was created in 1935 as a 50 square kilometre water reservoir for the Panama Canal and to generate electricity,” explains Christian.

Only very few clearings in the dense jungle of the Camino Reals in Panama allow a view of an almost always deserted landscape. Here the northern shore of Lake Alajuela; the Boquerón River meanders on the left of the picture.

A village as a gateway to the wilderness

We moor on the eastern shore of Lake Alajuela. Just a few metres from the shore, light brown stones stand out clearly from the ground. “These are the remains of the Camino Real,” explains Christian, “it was up to three metres wide here. The edge stones are still clearly recognisable.” He then rummages in his trouser pocket and shows us nails, spurs and fragments of horseshoes on the palm of his hand. “I found them all near here.”

Ok, and why was a stone path created? Christian explains further: “Without stones, the mules would have sunk into the mud or constantly slipped and slid. From tomorrow, in the rainforest, you’ll understand what I mean. Now it’s off to camp for the night.”

I am particularly fond of the black-bellied whistling ducks

The boat slowly travels along a side arm of the lake. Reeds, water lilies and other lake plants come closer. We flush out countless seabirds and my camera has a lot to do to capture ospreys, great egrets, bat falcons, cocoi herons, sunbitterns, snowy egrets and yellow-headed caracaras. Or at least to try.

They all forage in the shallow water for fish, frogs, lizards, earthworms, snails, insects, crustaceans or small invertebrates. I am particularly fond of the black-bellied whistling ducks with their crimson beaks and white circles around their eyes. I’m sure it’s also because they gave me what I think is a great photo.

I wasn’t so lucky with the wattled jacanas, which look like giant flying insects with their thin legs, unusually long toes, narrow bodies, white wing tips, red heads and bright yellow beaks.

Black-bellied whistling duck on Lake Alajuala. Males and females are externally indistinguishable.

The side arm becomes narrower and we pass a young yellow-crowned night heron peering for food from a villager’s boat. Huts become visible on a hill. “Quebrada Ancha, a last piece of civilisation before we finally plunge into the jungle,” comments Christian a little dramatically.

Quebrada Ancha is a positive example of sustainable community tourism. The residents are working hard to preserve and revitalise their cultural heritage. This includes maintaining 3 kilometres of the hiking trail and hosting guests like us. After a short tour of the village, we settle into our tents and then start our hike along the Camino Real.

“Chrrt … chip-chip”, a rusty-margined flycatcher sings from his perch above us

First steps on the Camino

The path is in surprisingly good condition, wide, dry, a little hilly. “Chrrt … chip-chip”, a rusty-margined flycatcher sings from his perch above us. We pass a tree with an impressive cluster of reddish-brown fruit a good metre long: a royal palm. “It was first described by Alexander von Humboldt,” explains Christian, “juice is made from these fruits and then fermented. The royal palm is also used for timber, the leaves for roofing. But it is most commonly used as an ornamental plant.”

Molinar Torribio knows the Camino Real like no other. He has already led or accompanied around 35 tours.

There is more to learn. We learn details about strangler figs, wild cashew trees and nance, a tree whose 2 to 3 centimetres fruits exude a flowery, fruity aroma. We taste them and savour a slight hint of cheese.

Suddenly, scarlet macaws whizz past us like red lightning bolts. “Probably a couple looking for food,” Alex surmises, “They live monogamously and stay together for life. Their roost tree can be up to 10 kilometres away from here.” A little later, we pass another strange tree with some light green fruits about 40 centimetres long. Christian grabs one of them and says: “Because they look like this, the tree is called a candle tree. The fruits are edible raw and can also be cooked.”

We step out of the forest into a clearing right next to Lake Alajuela. A boat takes us back to the village.

Howler monkeys grunt in the distance

Off into the rainforest

3.30 am. Howler monkeys grunt in the distance and roosters call out their first morning greetings in the village. After sunrise, we take the boat to the northern tip of the lake to resume yesterday’s route. We don’t disturb an elegantly wading little blue heron or the purple gallinule, which seems to be showing off a little with its bright ultramarine plumage, red beak with yellow tip and light blue forehead.

In over twenty expeditions, Christian Strassig succeeded in reconstructing almost the entire course of the Camino Real from the Pacific to the Atlantic coast.

Christian drops us off and returns by boat to pick us up again in Portobelo in a few days. After just a few minutes, Alex spots a yellow-throated toucan high up in the branches of a tree. Then a huge Caligo butterfly mesmerises us with its camouflage eyes, which are now particularly easy to see on the undersides of its closed wings.

One last time we catch a wide view of Lake Alajuela with the mouth of the Boquerón River, which we will later wade through several times. Then it gets dark: the rainforest swallows us up. After a short time on slippery paths, steep slopes and in rampant river valleys with constantly high humidity, everyone realises: this expedition requires willpower and stamina. Every 90 minutes or so, I wring out the soaked towel hanging around my neck.

It is a Geoffroy’s tamarin monkey

Irvin, Molinar’s son, discovers something high up in a tree. It is a Geoffroy’s tamarin monkey. Its torso is about 30 centimetres long, its tail is considerably longer at 40 centimetres. Its fingers and toes have claws instead of nails, which enables it to grip and climb better.

Around midday, we reach a clearing that reveals a last, completely intact section of the Camino. The chunky cobblestones lie close together, bordered by larger, higher kerbs. Alex comments: “This stretch of path is on private property. We can only hope that the local farmers, the campesinos, don’t remove the path to use the land for livestock farming.”

A Geoffroy’s tamarind monkey: just 30 centimetres tall, with a tail up to 40 centimetres long and a weight of around 500 grams.

Half an hour later, we take a break on a hill in front of a finca. It belongs to a campesino straight out of a picture book: Genaro Hernandez, 84 years old. He has lived here in the Chagres National Park since the early 1960s. From his horse, he looks down at us sweaty hikers with curiosity and a little amusement. “Everything green up to the horizon is mine,” he says, not without pride, “I can’t do anything else!” he laughs. That is a great understatement. He owns around 100 cows. He can fetch the equivalent of up to 1,300 euros for one animal.

“But the deforested rainforest is disappearing forever”

Later, while resting in the rainforest, Alex says: “Every year I see more clearings in the national park. I can understand the campesinos when they clear the rainforest to earn money from cattle farming. But the deforested rainforest is disappearing forever. We have to prevent that. Tourism is therefore an important alternative. It allows the campesinos to earn good money, preserve their values and culture and, above all, the rainforest.”

Under this open shelter, we protect ourselves from the rain, prepare food and attach hammocks. Dense rainforest can already be seen in the background.

Without the keen eyes of Alex, Molinar, Irvin and the porter and companion Eduviges de Leon, I would be lost. They spot the beautiful Adelpha cytherea butterfly and the tiny Micrathena sagittata spider for me. The bright colours of this animal, which is just one centimetre long, presumably help to attract prey, while the spines on its abdomen are used for defence.

And they spot the butterfly togarna hairstreak, a master of deception. Black hair tails and eyespots on its hind wings look like a false head. Potential attackers attack this camouflaged side and may only injure the wings instead of killing the butterfly.

After well over eight hours of net hiking time, we reach our camp for the night

Then finally, after well over eight hours of net hiking time, we reach our camp for the night: a field as a campsite and an open barn with a simple cooking area. The crystal-clear Boquerón flows nearby. All eight hikers jump in.

After more than eight hours of hiking on the Camino Real in temperatures of around thirty degrees, we reach our camp for the night. The Boquerón flows nearby, where we cool off.

In the web of the silk spider

The breakfast is surprising: cheese, sausage, butter, brown bread! Alex grimaces: “How can you eat that? It tastes like rotten wood.”

After an hour’s hike, the path leads over crimson-coloured soil. Alex explains: “This is sand from leafcutter ants. They carry it out of their burrows, which are deep and branched and harbour up to two million ants.”

I keep getting caught in spider webs, once in a particularly sticky one. “That was probably from a silk spider,” Alex surmises. “Their webs can reach two metres in diameter. The silk is stronger than nylon. Sometimes hummingbirds and young birds get caught in it.”

It demands sweat, strength and stamina

The clothes on our bodies are also sticky. Everyone walks in silence and sweating, focussed on the next step. The sound of the river accompanies us, complemented by chirping, squeaking, cracking, whirring, bird peeps, cicada buzzes and howler monkey grunts. The dense primary rainforest is unique. It demands sweat, strength and stamina. Without them, there is no experience, no depth, no adventure. For centuries, muleteers and soldiers perceived the same force of nature and heard the same spectrum of sounds.

Today, hardly any traces of the Camino can be found in the rainforest. The stones have slipped away, overgrown, buried. This too is an experience: everything created by man is ephemeral here.

Iron artefacts found between the cobblestones of the Camino Real: Fragments of horseshoes and nails (Photo by Christian Strassnig).

Eduviges discovers a Jesus Christ lizard in the pebbles on the riverbank. We approach and recognise the cartilaginous crest on the back of its head. The young animal still trusts its camouflage, but then dashes off! It races across the river on its hind legs, a fascinating sight. Its large hind feet have toes with skin flaps that fold out when running and increase the surface area. Its light body and powerful hind legs generate enough buoyancy to prevent it from sinking in.

Alex discovers another camouflage artist in the brown foliage

An hour later, we hear the rumble of thunder. “No rain, please,” I hope. Fortunately, it stays dry. I don’t want to imagine how the path would turn into a muddy wasteland in heavy rain. Then I hear a hacking knock. A black-cheeked woodpecker is searching for ants, beetles or larvae in the bark of a tree. Minutes later I see a passive colleague: a broad-billed motmot. It sits motionless in the tree and waits for insects to buzz by.

Alex discovers another camouflage artist in the brown foliage. I wouldn’t have recognised it without his help. It is a false leaf katydid, a species of grasshopper.

A False Leaf Katydid (Orophus tesselatus), which refers to their leaf-like appearance.

Days later he died of an intestinal infection

One harbour, a thousand stories

The last day of walking takes us along the Cascajal river. After six hours, we reach a main road where a bus takes us to the end point of the Camino Real: the bay of Portobelo, discovered by Columbus in 1502. This is where Spanish ships picked up the treasures transported along the Camino and sailed them to Europe.

Portobelo is a UNESCO World Heritage Site, a place steeped in history, where you can travel back in time in its defences, in the royal customs house and in its squares. The English pirate Francis Drake, who gave his name to the Drake Passage, attacked Portobelo for its treasures. Days later he died of an intestinal infection and was buried off the coast of Portobelo.

A turkey vulture over Panama City. Its wingspan can be up to 2 metres. In areas colonised by humans, they often eat dead animals.

Now I’m sitting on the hotel terrace, showered, with a cold beer, with my fellow hikers. We look out over the bay of Portobelo. The hardships of the hike become transfigured. We joke and ponder: Four days from the Pacific to the Atlantic, centuries of breathing history in colonial buildings, fabulous silver and gold treasures, intact rainforest, fascinating flora and fauna, and yes, a little shaking of your own limits. You can really only experience this here, on the Camino Real.

Read now:

Pure inspiration

My new media kit 2025

< 1 Min.In this brand new 28-page media kit, I show you my work as an adventure journalist and speaker: Expeditions, travels, challenges – everything that excites me. Let yourself be inspired.

Iceland extreme: volcanic eruption and ice bathing

Iceland photo gallery

2 Min.Iceland – island of extremes. On the largest volcanic island in the world, we are fascinated by the eruption of the Fagradalsfjall volcano. And we learn to ice bathe, for minutes! Then a lagoon bath, glacier tour and ice cave visit – an unforgettable short adventure!

Where to experience your green miracle

Costa Rica – Fliers, frogs, sloths

20 Min.So small and yet full of records! In relation to its small area, Costa Rica has the highest biodiversity in the world. 99 % of its electricity is generated from renewable sources. And in the prestigious Happy Planet Index for well-being and sustainability, it has been ranked first for years, ahead of 139 countries.