Published in:

Germany’s biggest nature travel magazine

10 pages | text & photographs

Staffa: Geology meets romance

“In comparison, what are the cathedrals or palaces built by humans? Mere models or gimmicks, imitations, when compared with those of nature.” So enthused the British naturalist Joseph Banks on 13 August 1772 about his discovery of a geological wonder forest made up of thousands of basalt columns on the uninhabited Hebridean island of Staffa.

251 years later, in September 2023, my wife Annette and I hop over the hexagonal bars that protrude from the sea like organ pipes. We grab a steel line that leads us to Fingal’s Cave, an 80-metre-deep, cathedral-like grotto completely lined with anthracite-coloured basalt.

The narrowness of the cave amplifies the acoustics and makes the water roar

Theodor Fontane called it ‘a tightly bound bundle of stony fir trees’ in his 1860 travelogue ‘Beyond the Tweed’. The sea water whipped up by the wind whips, beats and foams in the cave. The spray transforms the stones into shiny black lacquered surfaces. The narrowness of the cave amplifies the acoustics and makes the water roar.

In the Romantic period, nature played an important role as a place of longing, mysticism and contemplation. Even then, Fingal’s Cave offered a little bit of everything. In 1832, William Turner manoeuvred his easel in front of the cave to immortalise its entrance on canvas. Felix Mendelssohn Bartholdy had already visited the island three years earlier. “In Fingal’s Cave, I immediately realised the theme of the overture,” he wrote to his sister Fanny. However, it would be another four years before his ten-minute opus 26, the ‘Hebrides Overture’, was premiered.

Fingal’s Cave is named after the legendary hero Fingal, a character from the Scottish writer James Macpherson.

We stroll through the greenish-yellow grass meadows of the 200 by 600 metre island. The occasional magenta-coloured Massliebchen sway in the strong sea breeze.

A few minutes later, our boat pushes off from the wonder island. I think of the many artists of past centuries, of the intensity of their feelings, from which many of them created masterpieces. I have little in common with them – except perhaps this look. A child waves to the island and shouts “Bye bye, Fingal’s Cave!” Staffa is behind us.

Once someone from the mainland stole a quad bike here

Lismore: Island without thieves

“We don’t have police on the island. Why should we? The last offence was a long time ago. In 1956, an islander stole tools from a shed. But police officers from the mainland visit us once a year. They check cars and gun licences. They book their ferry passage two weeks in advance. Word gets around quickly and gives everyone enough time…” now the island guide Robert Smith laughs, raises both arms, waves both index fingers and says: “… to prepare.” Another island original joins in. Then you hear phrases like “Hidden in the shed” or “If they knew”. Laughter again. Robert continues: “We take good care of each other here. Once someone from the mainland stole a quad bike here. The ferry captain recognised the bike, confronted the thief and cleared the matter up with his crew. The thief left the boat empty-handed – and with a few scratches.“

Annette walks along the historic, whitewashed cottages on the island of Coll.

Robert steers his Land Rover Defender down a gentle slope over a gravel track. Countless such hills, on whose fertile limestone soils barley, potatoes and oats thrive, characterise the landscape of the 16-kilometre-long and approximately 1.6-kilometre-wide island. The name Lismore comes from the Gaelic word “Lios Mòr”, which means “large garden”. Cows and sheep graze on the pastures. Small villages and scattered houses nestle on the coast, with fishing boats bobbing in front of them to the rhythm of the tides.

‘Dun’ is also related to the English ‘town’ and the German ‘Zaun’

Robert points to an abandoned round stone tower perched on a hill. “That’s a broch, a dwelling and defence structure built without mortar between 500 BC and 500 AD. These brochs only exist here on the west coast of Scotland.” The island has been inhabited for a long time. In 1974, a polished stone axe dating back around 5,500 years was found. In the Bronze Age, cairns were created, mostly burial sites made of carefully piled up quarry stones or rubble. 14 of them are preserved on Lismore.

After that, until the early Middle Ages, local tribal leaders built duns: round dwellings, drystone castles and settlements, many of them on hills. Over 800 duns have been identified in Scotland, and six well-preserved ones with names are known in Lismore. Many place names contain ‘dun’ or phonetically similar elements, e.g. Edinburgh, London, Verdun and Thun in Switzerland. ‘Dun’ is also related to the English ‘town’ and the German ‘Zaun’.

Shepherd Arthur and his collie called Misty.

Shepherd’s hour

A shrill whistle. With their tongues outstretched, three dogs drive a flock of 46 sheep across a hilly, green-brown meadow. Behind them, white whitecaps on turquoise-coloured ocean waves. Shepherd Arthur Scott watches the action. Then the grey-clad, slim man in his mid-fifties raises his shepherd’s crook, shouts and whistles commands to his dogs. The flock sets off to graze another piece of pastureland. It’s a big game for his three collies Misty, Fly and Tam. “Even as a young lad, I worked as a shepherd in the highlands,” says Arthur. “I travelled the mountains and hills all over Scotland, shearing sheep, collecting wool and helping with lambing.”

Collie Misty senses the opportunity, joins him and lets herself be cuddled

Even today, his working day often starts before sunrise. Arthur checks the fences, makes sure the water is fresh and sets off with his flock when the dew is still glistening on the grass. Looking at the animals, he says: “In September, parasites attack more and more animals. I’ll soon have to give them a worming treatment. When the pastures have less nutrients, I feed hay and mineral pellets.” Arthur lies down on the grass to rest. Collie Misty senses the opportunity, joins him and lets herself be cuddled. Arthur’s working day ends in a few hours. Characterised by physical labour, but also by a deep connection with nature and its animals.

Annette enjoys the spectacular view of Loch Katrine from Ben A’an Mountain, a popular excursion destination.

Ben A’an: Summit view of the loch

It’s getting steeper. About an hour ago, in the car park on the A821, Annette and I strapped on our daypacks. On the way to the 454 metres high Ben A’an, we passed oaks, pines and ash trees and marvelled at carpets of mosses, ferns and wildflowers. We crossed the Allt Inneir stream, saw dragonflies and fleeing squirrels. Now the path, which climbs like a staircase, requires much more stamina.

A hawk circles in the sky

The trees are thinning out, it seems as if they have been cut down here. We take a breather and look around. Here, in the Trossachs, also known as ‘miniature Highland’, the National Park is a mosaic of gentle valleys, hills, ancient forests and wide lakes. A hawk circles in the sky. We continue on our way.

Half an hour later we reach the pyramid-shaped summit of Ben A’an, today cloudless. We enjoy a clear 360-degree view over the elongated Loch Katrine, the smaller south-eastern Loch Achray, the nearby 729-metre-high Ben Venue and the 954-metre-high Ben Lomond in the distance.

In the Scottish Highlands: a red deer shows off its impressive antlers. And perhaps his sense of humour.

A thrush calls us names. We must have invaded their territory. The ground is still damp from the rain. We take a deep breath before descending. The scent of alpine plants, heather and grasses fills our noses and lungs. This is nature in all its freshness.

No, we didn’t see a warning sign. No prohibition sign either.

Buchanan Castle: Mysticism with moss

No, we didn’t see a warning sign. No prohibition sign either. Annette and I are a little surprised that this enchanted castle ruin is so easily accessible: Buchanan Castle, a dilapidated jewel in the middle of nature. The walls, up to three storeys high, are completely preserved.

“They’re solid,” we are told by a young, morbidly dressed and made-up couple who take photos of each other with mobile phones in gothic poses. Nevertheless, we are careful, walk cautiously, don’t touch any load-bearing walls and don’t climb any stairs. The main building is around 60 metres long and 30 metres wide. The height of the building varies, reaching up to 20 metres in the towers. Annette and I get a sense of the immense wealth of the family that once lived on this estate.

The roof of Buchanan Castle was removed in 1954 and since then the property has fallen into disrepair, but its wonderfully spooky charm remains.

The land on which the ruins stand has belonged to the Buchanan clan since the 13th century. However, their main line died out in 1682. The clan chiefs were heavily in debt and sold the land to the Montrose family shortly afterwards. Buchanan Castle was built between 1852 and 1858 under the supervision of architect William Burn.

The extravagant Scottish Baronial-style country estate is characterised by residential towers, battlements, small turrets on corners and walls, stepped gables and a large watchtower. Buchanan Castle was sold in 1925 and converted into a hotel. During the Second World War, it was used as a military hospital. In 1941, after his flight to Scotland, Rudolf Hess was treated here. The main roof was removed in 1954, after which the building fell into disrepair.

Ivy envelops stones and walls like a green curtain

The smell of mouldy leaves and moss fills our nostrils. A thick layer of leaves covers the ground like a soft carpet. Ferns grow between the rubble, ivy envelops stones and walls like a green curtain. Small plants sprout from cracks in the walls. Birch and oak trees grow in the long corridors and the once magnificent halls and rooms. Their branches poke through broken windows, old door frames and crumbling roofs. Sparrows, thrushes and bats flutter through the air.

Annette and I are delighted with the mixture of ruins, tranquillity and nature. It creates a unique atmosphere that, with a little imagination, allows you to travel back to a fairytale past. The silent embrace of nature here shows every visitor that everything is fleeting, even the most magnificent buildings.

View over Tobermory, Isle of Mull.

Visibility and expanse

“If you don’t like the weather, wait five minutes.” grins the bearded waiter at the Isle of Mull Hotel & Spa. He serves Tobbermory whisky, Earl Grey tea and Dundee cake, the traditional Scottish fruit cake. Our faces brighten. Seconds before, we were still looking glumly through the large patio windows at endless threads of rain.

We chat a little with the very nice man in his mid-thirties. Suddenly I feel a rising warmth on my back. I turn around and see rays of sunlight breaking through the grey sky. The waiter points towards the sun and comments with a smile: “As I said, if you don’t like the weather…”.

Slow down, say hello, pass, drive on

Sun at last! We have to make the most of it, sunlight was in short supply today. Annette drives the hire car along the coast of the Isle of Mull. A sign warns of crossing otters. A little later, eight pheasants wobble across the road. They love this semi-open landscape with sparse woodland, lots of undergrowth and reeds. We pass an old, decommissioned red telephone box, which now houses a defibrillator. The road is narrow and requires the same procedure for every rare oncoming car: Slow down, say hello, pass, drive on.

Majestic cliffs and green slopes on the coast of the Isle of Mull.

I can well understand William Turner, Caspar David Friedrich and the other landscape painters of the Romantic period. Who doesn’t fall under the spell of this dramatic, expansive nature? The sun swaps gently rolling hills for lush yellow and green. Dark clouds quickly pass by in the blue sky. In the distance, light-coloured curtains of rain hover in front of black cliffs and over the dark sea.

Nature is stable in itself and defies every storm with stoic composure

Wild, untamed, beautiful. Calming? Intimidating? Perhaps both. Science writer Bas Kast calls nature a place of calm and resilience. Nature is stable in itself and defies every storm with stoic composure. Perhaps this rubs off on us when we spend time in nature.

The discoverer and surveyor of Fingal’s Cave, Joseph Banks, wrote in his ‘Journal of a Voyage’ in 1772: “How generously Nature rewards those who study her marvellous works.”

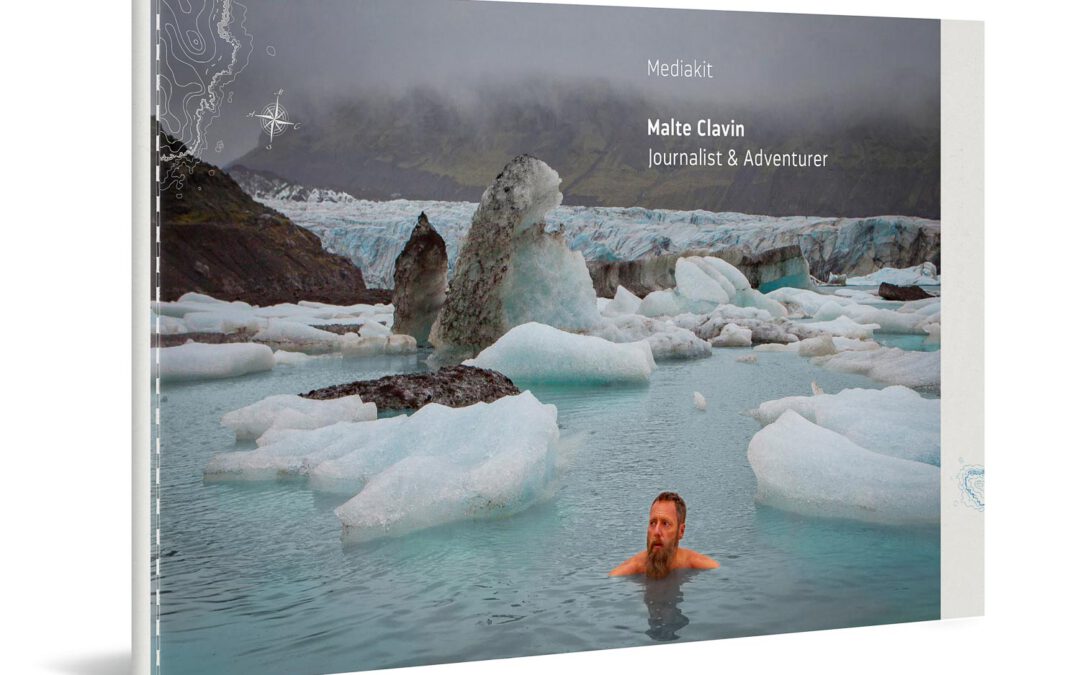

Read now:

Pure inspiration

My new media kit 2025

< 1 Min.In this brand new 28-page media kit, I show you my work as an adventure journalist and speaker: Expeditions, travels, challenges – everything that excites me. Let yourself be inspired.

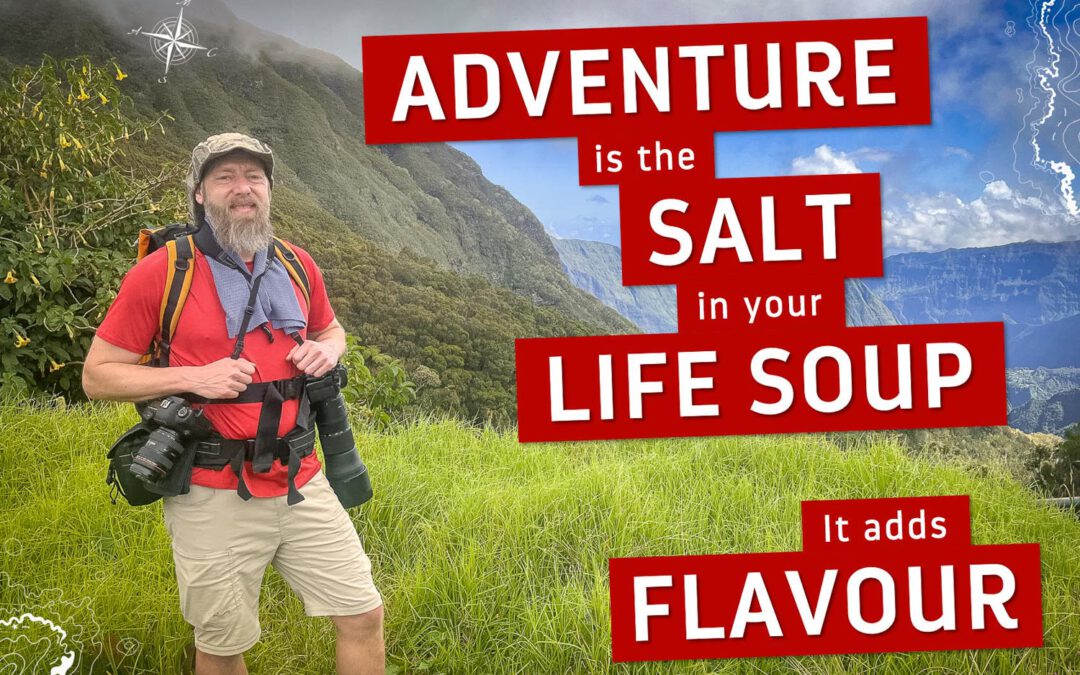

Food for thought

Adventure is the salt in your life-soup

2 Min.Adventure is like salt in the soup of life. It adds flavour.

Where to experience your green miracle

Costa Rica – Fliers, frogs, sloths

20 Min.So small and yet full of records! In relation to its small area, Costa Rica has the highest biodiversity in the world. 99 % of its electricity is generated from renewable sources. And in the prestigious Happy Planet Index for well-being and sustainability, it has been ranked first for years, ahead of 139 countries.