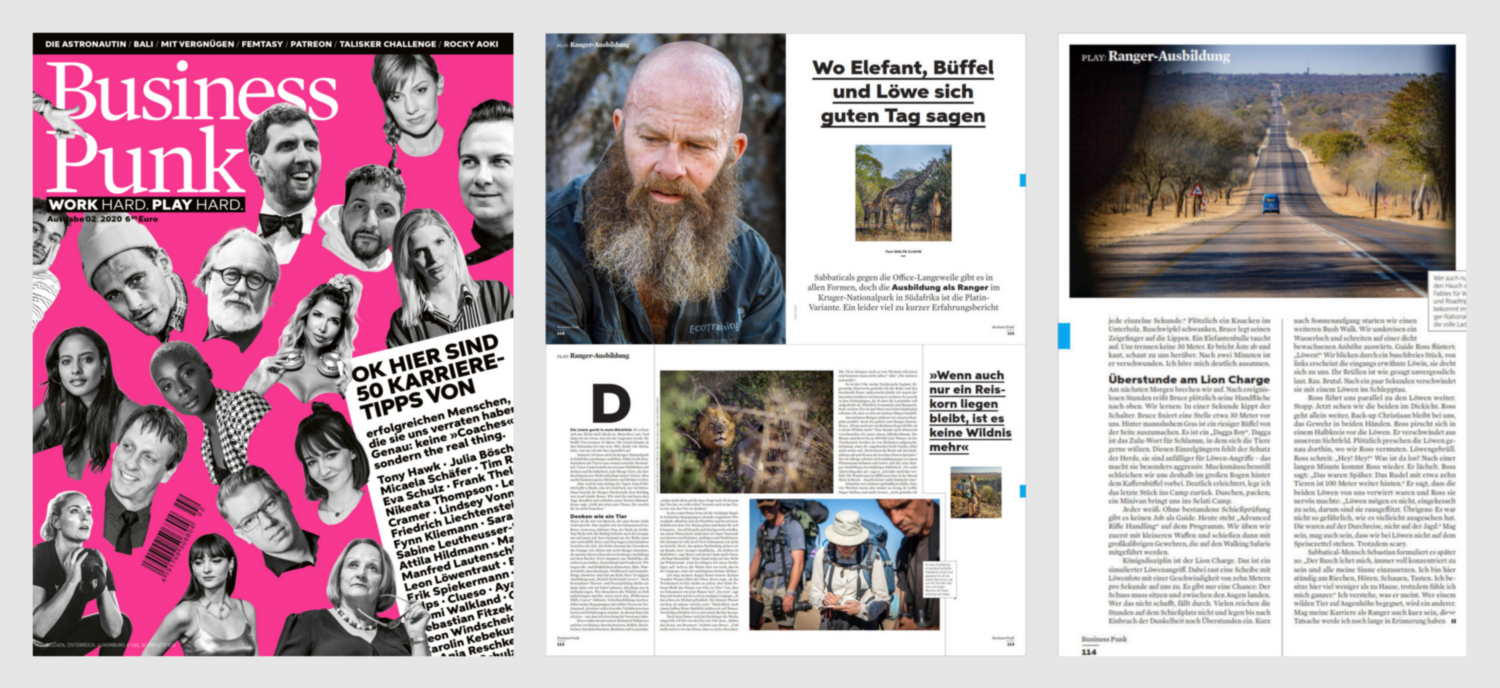

Published in:

Germany’s business magazine for tomorrow’s CEOs

Feature | 5 pages | text & photography

Where elephant, buffalo and lion say hello to each other

The lioness comes into my field of vision. She looks around, looks directly at me. My heart races. And then she does something I will never forget: She roars! She is 25 meters away. The lioness could be with me in three seconds. Shit, I think. My goodness, what am I doing to myself here?

But at night, elephants and hyenas like to pass by.

Answer: I’m training to be a ranger in Kruger National Park in South Africa. The confrontation with animals is a central part of the training.

Our camp consists of a few wooden huts with stilts and thatched roofs, lots of animals walking through. Not necessarily always lions. But at night, elephants and hyenas like to pass by.

Bruce demonstrates how to ignite fire with wood, elephant dung, skill and patience.

But back to the start of the day: For breakfast we have rusks, a kind of biscuit, only much harder. Then the young rangers listen to the briefing from lead guide Bruce: “We’ll be outside for the next three days, sleeping out in the open sky. Bruce says, “Give me your watches now. You won’t need them there.”

Third in line is the greenhorn of the group: me.

Thinking like an animal

Bruce is the kind of person you’d better not contradict. So we trudge off in single file: Bruce in front, Nep, the back-up guide, behind. Nep looks around at the group every fifty paces, making sure no one steps out of line or falls behind. Bruce and Nep carry loaded and primed rifles. Third in line is the greenhorn of the group: me. Behind me are six ranger candidates, most of them with weeks of training under their belts. Two are from South Africa, the others from India, Germany and France.

On the way to the shooting range Moholoholo. The distances are long in South Africa.

We are wearing olive and khaki clothes, hats, hiking boots, and carrying backpacks, hydration bags and sleeping mats. Some of the aspirants are almost at the end of their 55-day training to become “FGASA Field Guide Level 1”. After passing the theory and practical exams, they are allowed to take guests on safari, but only in off-road vehicles.

“Put yourselves in the animal’s place. Learn to think like the animal.”

Those who want to introduce visitors to the wilderness on foot must complete the Wilderness Skills Course, which includes shooting training. The focus here is on encounters with wild animals; candidates are supposed to learn correct behavior and gain experience. That’s the course I’m in now – except that I don’t have any prior knowledge.

Bruce circles the footprints and droppings of hyenas, bushpigs, buffalo, bushbuck, porcupines, elephants and leopards with his wooden stick: “Don’t pay attention to the tracks alone. Ask yourselves: Where does the animal come from, where is it going? Put yourselves in the animal’s place. Learn to think like the animal.”

A look that no one in our group will ever forget: we are being assessed by a wild lion. Photo by Stephane Zemiro.

During the first break, I learn the most important rule: never run away in critical encounters! Whoever runs away reveals himself as a flight animal and is lost. Instead, give the animal space and claim space for yourself – this should create respect and balance.

Then at a waterhole we discover thousands of tracks of elephants, antelopes and rhinos. The savannah is full, but we don’t get to see any animals. Yet. Late afternoon we reach the edge of a huge sandy area. “That’s Zimbabwe over there,” Bruce says, then points east, “That’s Mozambique.” His hand points to a spot on the desert’s edge, “And that’s where we’ll camp for the night.”

They can smell water, there should be some.”

“Oh, I see, the desert here in front of you, that’s the Limpopo, one of the mightiest rivers in Africa.” I can hardly believe my eyes: Not a drop of water does the river carry. Bruce says, “There’s nothing here in the dry season, but by the end of February the water is flowing from bank to bank.”

Fine, but where are we going to get water now? “Up ahead,” Nep says, pointing to a hole in the sandy Limpopo, “an elephant has already dug there. They can smell water, there should be some.”

Indeed, after half a meter of digging, we hit water. We carefully scoop it out with a cup. After dinner, the night camp is divided into watches, and it’s my turn from three to four o’clock. “Keep the fire burning,” Bruce instructs us. “And stand in front of the fire so it lights you up.”

Only a few meters behind the Punda Maria Gate, an entrance to the Klrüger National Park, I meet a giraffe mother with her calves.

“So the animals can spot you from a distance and then don’t come any closer.” All of them? “Most of them, anyway.”

It’s three o’clock, my vigil begins. Strange: on the one hand I enjoy the silence and the crackling fire, on the other hand I think I hear much more intensely because of the lurking dangers: It rushes in the auditory canals, as if the volume is turned up full there.

Suddenly grumbling and rumbling. Fuck, what animal is that? After two seconds of shock, I realize that it’s my stomach.

“If even a grain of rice is left lying around, it’s no longer wilderness.”

The next morning we clean our resting place meticulously. That, too, is part of being a ranger. Bruce: “If even a grain of rice is left lying around, it’s no longer wilderness.”

An hour after setting off, we take a breather under a baobab tree. The trees store up to 100,000 liters of water. In the dry season, they are frequented by elephants.

Sebastian, one of the prospective field guides, enlightens me further: “They scratch the bark with their tusks and eat the moist fibers underneath.”

During the Wilderness Skills Course a lot of knowledge is taught one cannot find in any textbook. Kim records the newly acquired insights in her notebook.

The 46-year-old works as a product manager at a pharmaceutical company and is taking a one-year sabbatical for his ranger training. “It all started 10 years ago,” he says. “I fell in love here. The migration of millions of wildebeest in the Maasai Mara in Kenya – no one goes out unimpressed.”

After uneventful hours, Bruce suddenly jerks his palm upward.

Sebastian has been in Africa regularly since then. But three or four weeks were always too little. He wanted to stay longer and learn more. “Now I enjoy every single second.”

Suddenly, a crackling in the undergrowth. Bush tops swaying, Bruce puts his index finger to his lips. A bull elephant emerges. Less than 30 meters away. He breaks branches and chews, looking over at us. After two minutes he has disappeared. I hear myself exhale clearly.

Overtime at the Lion Charge

The next morning we set off after a filling of porridge. After uneventful hours, Bruce suddenly jerks his palm upward. That’s how it is in the wild, in a second the switch flips.

Close to our second camp, Backup Guide Nep searches the wilderness for animals and discovers a herd of Cape buffalo.

Bruce fixes a spot about 30 meters in front of us. Behind man-high grass, a huge buffalo can be made out from the side.

It is a “Dagga Boy.” Dagga is the Zulu word for mud, in which the animals like to roll. These solitary animals lack the protection of the herd and are more susceptible to lion attacks – which makes them particularly aggressive.

There is only one chance: the shot must be accurate and land between the eyes.

Quiet as mice, we therefore sneak past the Cape buffalo in a wide arc. Clearly relieved, I make the last stretch back to camp. Shower, pack; a minivan takes us to Selati Camp.

Everybody knows: Without passing the shooting test, there is no job as a guide. Today, the “Advanced Rifle Handling” is on the program. We first practice with smaller weapons and then shoot with large caliber rifles that are carried on the walking safaris.

The supreme discipline is the Lion Charge. This is a simulated lion attack. In the process, a disc with a lion photo races toward us at a speed of ten meters per second.

There is only one chance: the shot must be accurate and land between the eyes. If it doesn’t, you fail. For many, the hours on the shooting range are not enough and they put in overtime until after dark.

I enjoy fantastic views in the Blyde River Canyon.

Shortly after sunrise we start another bush walk. We circle a waterhole and walk out on a densely overgrown hill. Guide Ross whispers, “Lions!” We look through a bush-free patch, from the left appears the lioness mentioned at the beginning, she turns to us.

Her roar is unforgettable: Loud. Raucous. Brutal. After a few seconds she disappears with a lion in tow.

Suddenly, the lions rush right to where we think Ross is.

Ross leads us on parallel to the lions. Stop. Now we see the two in the thicket. Ross continues alone, back-up Christiaan stays with us, rifle in both hands. Ross stalks in a semicircle in front of the lions. He disappears from our field of vision. Suddenly, the lions rush right to where we think Ross is.

The lions roar again. Ross yells, “Hey! Hey!” What’s going on? After a long minute, Ross comes back. He smiles. Ross says, “They were scouts. The pride of about ten animals is 100 yards back.”

An elephant frightens this young zebra, which took a nap in the dense grass. It trudges over to us and looks at us lost. “It’s looking for its herd,” says Bruce, “the little one is just three or four months old.” Slowly it trots on and disappears into the bushes. Good luck, little zebra.

He says that the two lions were confused by us and Ross made them nervous: “Lions don’t like to be boxed in, that’s why they scampered out. By the way, it wasn’t as dangerous as it might have looked. They were passing through, not hunting.” Maybe, maybe not, we’re not on the menu for lions. Still scary, though.

Whoever has been eye to eye with a wild animal, becomes one.

Sabbatical man Sebastian later puts it this way: “The bush teaches me to always be fully concentrated and to use all my senses. I’m constantly smelling, hearing, looking, touching here.

I possess much less here than at home, yet I feel more whole.” I understand what he means. Whoever has been eye to eye with a wild animal, becomes one. May it be that my career as a ranger is short, I will remember this fact for a long time.

Read now:

Pure inspiration

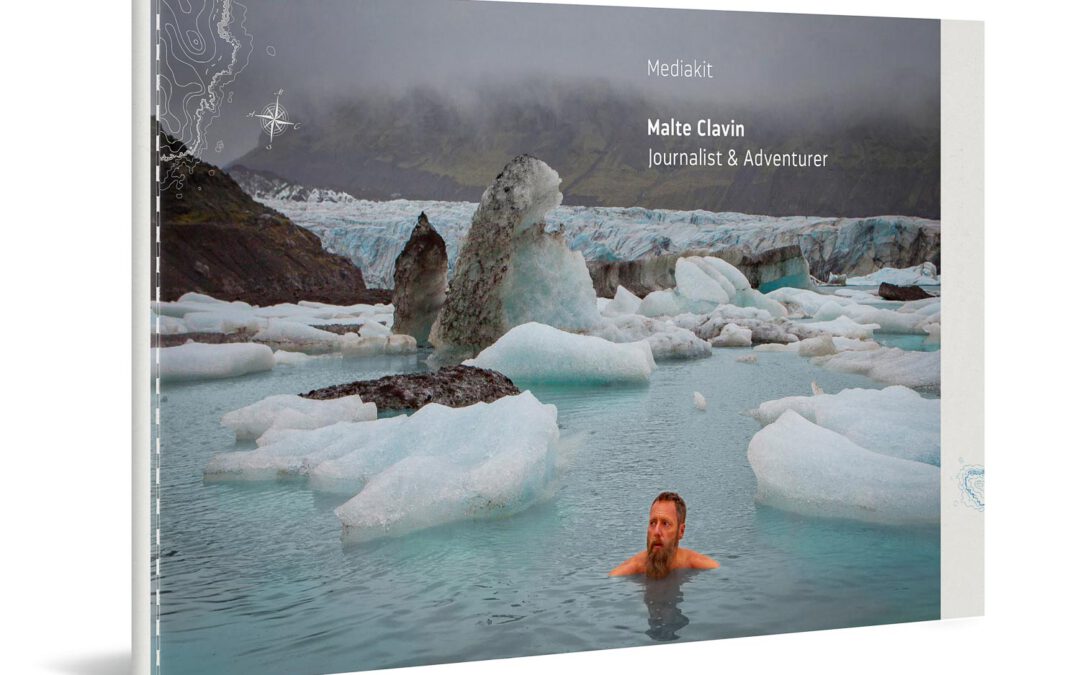

My new media kit 2025

< 1 Min.In this brand new 28-page media kit, I show you my work as an adventure journalist and speaker: Expeditions, travels, challenges – everything that excites me. Let yourself be inspired.

Ranger Training in South Africa

Something is up in the bush

16 Min.Exploring the wilderness on foot in the midst of lions, elephants and buffalo? You can learn to do that. In summer 2019, I will join a field guide course in South Africa.

Ranger training on the edge of the Kruger National Park

South Africa photo gallery

< 1 Min.Exploring the wilderness on foot in the midst of lions, elephants and buffalo? You can learn to do that. In summer 2019, I will join a field guide course in South Africa.