Published in:

Germany’s biggest nature travel magazine

12 pages | text & photographs

A river journey to the heart

“The Napo is more than just a river – it is the beating heart of our country, the lifeline of the peoples of the forest,” wrote the Ecuadorian scholar Pedro Maldonado in the 18th century. His words echo in my mind as an 18-metre motorboat carries my companions – eight travel agents and journalists – and me downstream along Ecuador’s longest river, the Río Napo.

Through narrow, dark waterways, we travel into the jungle

The north and south banks of the river lie between one and three kilometres apart. Natural foam, formed by churned-up organic nutrients, dances on the water’s surface. Along the banks, a thousand shades of green shine vibrantly.

After two hours, we dock and walk a kilometre along a wooden plank path before switching to canoes that take us deep into the jungle through narrow, dark waterways.

The largest kingfisher in the Amazon: the Ringed kingfisher.

“The darker water colour is due to a high content of humic substances,” explains our naturalist guide, Christian Zavala. “They form as leaves, wood, roots, and other plant and animal matter decompose.” As he speaks, our boat startles a jet-black Greater Yellow-headed Vulture, its light grey head and neck feathers forming a mask-like contrast.

Their incessant chatter resembling a never-ending argument

We spot the largest kingfisher in the Amazon, the Ringed Kingfisher. Palm-sized dragonflies dance in the humid air. A massive beehive perches on a branch above us. Two Red-bellied Macaws fly past, their incessant chatter resembling a never-ending argument. A solitary Ecuadorian White-fronted Capuchin monkey moves sluggishly through the treetops. “A monkey left alone,” Christian murmurs, “is usually either sick or old.”

Twice a day, guests at Sacha Lodge have the opportunity to experience fascinating nature up close.

The channel suddenly opens onto Pilchicocha Lake, where I catch sight of a wooden house at its far end—our destination for the day: the Sacha Lodge. A shrill whistle pierces the silence. Hidden in the lakeside thicket, a young Giant Otter calls for its parents. These animals can grow up to two metres long and consume eight to ten kilograms of fish daily.

A model of sustainable tourism

Swiss Vision in the rainforest

Founded in 1992 by Swiss entrepreneur Arnold ‘Benny’ Ammeter, Sacha Lodge is a model of sustainable tourism. Providing employment for over 60 local families, it is the largest tourism-sector employer in Ecuador’s Amazon region, offering an alternative to environmentally destructive activities such as deforestation and oil extraction.

The Sacha Lodge restaurant as seen from Lake Pilchicocha. (Photo by Sacha Lodge)

Within this 5,000-hectare reserve, there is no hunting, logging, drilling, or any form of extraction. No animals are fed or baited. Ninety percent of the staff come from local communities, and the lodge prioritises ecological, biodegradable, and reusable materials. Fish, fruit, and vegetables are sourced locally whenever possible.

An acoustic amphitheatre of the surrounding rainforest

From the moment we step out of the canoes, the hospitality of the staff, their pride in their culture, and their respect for the environment are palpable. We are led across a wooden gangway to an open-air cabana, where meals are served—and where a cocktail or two may be enjoyed before or after dinner. The cabana hovers above the black waters of Pilchicocha Lagoon, its atmosphere enriched by the deep calls of tree frogs and the chirping of cicadas, forming an acoustic amphitheatre of the surrounding rainforest.

Night monkeys are the only nocturnal monkeys. Their weight varies between 0.7 and 1.2 kilograms.

The biodiversity around the lodge is extraordinary. Eight species of monkeys inhabit the area, from the tiny Pygmy Marmoset, weighing just half a pound, to the cacophonous Red Howler Monkey, weighing 17 pounds.

Lucky visitors might even spot an anteater, a three-toed sloth, or an ocelot

Night monkeys live in pairs, while Squirrel Monkeys travel in groups of over 150 individuals. In addition to primates, around 60 other mammal species and 50 bat species reside here. Lucky visitors might even spot an anteater, a three-toed sloth, or an ocelot.

On the narrow waterways not far from Sacha Lodge you can observe birds, monkeys, amphibians and much more.

First steps in and above the jungle

The first walk to my hut along the elevated wooden walkway takes me through dense, flooded palm forest and artificial ponds. I’m astonished to see a Spectacled Caiman raising its head from a pond, seemingly grinning at me.

Thermoregulation, is essential for cold-blooded animals

Nearby, a Yellow-spotted River Turtle warms itself on a rock. This process, known as thermoregulation, is essential for cold-blooded animals like turtles, as they cannot maintain a constant body temperature like mammals or birds.

A yellow-spotted river turtle.

Arriving at my comfortable hut, I immediately settle into the hammock on the terrace. “Just take it all in, let the rainforest seep in slowly,” I think to myself. Then, a rustling in the undergrowth catches my attention. A few of the delightfully inquisitive Ecuadorian Squirrel Monkeys scurry past my hut. One approaches and curiously studies me with quick, nervous head movements before vanishing into the dense greenery.

Ecuadorian Squirrel Monkeys have a body length of about 30 cm and a tail of approximately 44 cm. Their fur is olive-grey with an orange hue, while their feet and hands are a striking yellow-orange.

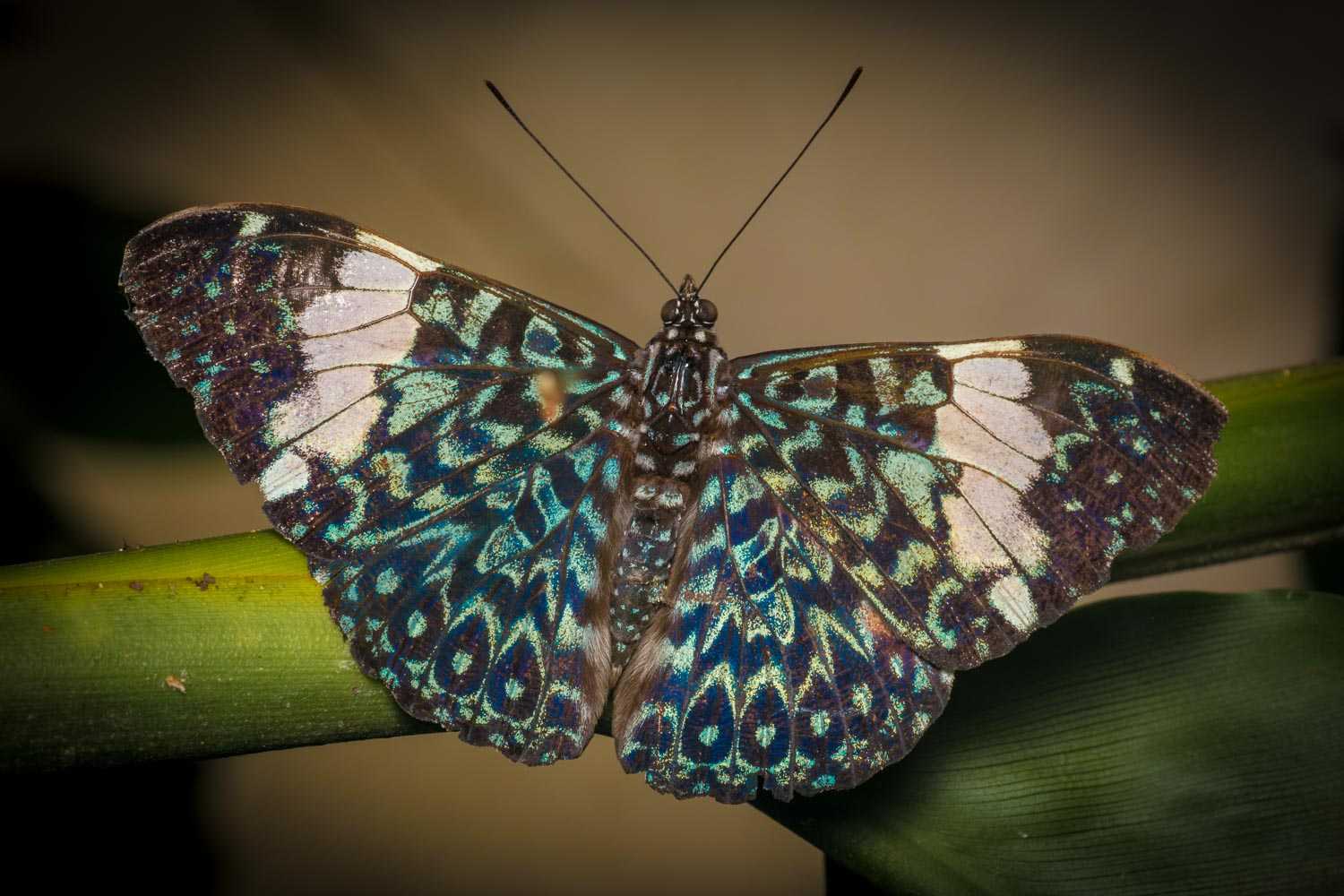

Hundreds of colourful butterflies flit from flower to flower

I slip into knee-high rubber boots—time for the first rainforest exploration. On my way to the meeting point, I pass Sacha Lodge’s ‘flying room’—the butterfly farm. One of the largest in Ecuador, it raises around 40 native species. Hundreds of colourful butterflies flit from flower to flower. Among them, Glasswing Butterflies, whose transparent wings provide excellent camouflage, and the elusive Blue Morpho Butterfly, whose shimmering turquoise wings prove impossible to capture with my camera.

An Ecuadorian squirrel monkey. I took this photo from the terrace of my little house at Sacha Lodge.

I have more luck with a butterfly from the Hamadryas genus and the large Caligo oileus, also known as the Oileus giant owl. These gentle giants have a wingspan of up to 20 cm, and the large eyespots on their wing undersides deter predators.

During our initial exploration, we take care not to step on the many marching armies of Leafcutter Ants. Christian explains: “In a primary rainforest like this, less than one percent of sunlight reaches the forest floor! That’s why there’s very little undergrowth, making it surprisingly easy to move around.”

Less than one percent of sunlight reaches the forest floor

Suddenly, a towering steel structure looms ahead—the staircase leading to a canopy walkway! This 275-metre-long bridge, suspended 36 metres above the forest floor, offers an excellent vantage point for spotting wildlife that is rarely seen from below. The sturdy walkway is supported by three metal towers. Now, at sunset, the light is particularly rich and silky.

A butterfly of the genus Hamadryas (Nymphalidae).

From the top, I can see the voluminous crowns of Kapok trees, the tallest trees in the rainforest—shaped like giant broccoli heads. They are considered sacred, believed to watch over all beneath them. Christian adds: “They are also home to jaguars. Did you know jaguars can dive four to five metres deep? They even eat turtles, cracking their shells, and sometimes hunt caimans by biting into their skulls.”

Plumbeous Kite – its name derives from its unique flight style

Now, we spot a Plumbeous Kite. Its name derives from its unique flight style—it glides effortlessly, appearing almost motionless in the air. As dusk fades into darkness, we return to the lodge, accompanied by the growing symphony of nocturnal creatures awakening.

One of the special features of Sacha Lodge is this 36 metre high and 275 metre long suspension bridge over the rainforest.

Bird spectacle in the Kapok tree

Paddling through the narrow tributaries of the Napo River feels like gliding through a green wellness oasis. After half an hour by boat and a ten-minute walk, it emerges before us: a 43-metre-high observation tower, built around a massive Kapok tree. Like a climbing vine, the steel staircase winds its way into the sky. As we ascend, enormous branches spread out, adorned with bromeliads, mosses, vines, ferns, and lichens.

A deep, guttural roar cuts through the morning mist

A deep, guttural roar cuts through the morning mist: Howler Monkeys! Their powerful calls, used to mark their territory, echo up to five kilometres through the rainforest. Once at the top, our guide Christian explains, “Of Ecuador’s 1,600 bird species, 587 have been recorded in the Sacha Lodge area—37 percent of the country’s total. That’s nearly seven percent of all bird species on Earth!”

A black tailed tityra (Tityra cayana).

As the morning light intensifies, the first birds appear. Christian, with unwavering enthusiasm, points out species at an astonishing pace, naming them faster than my brain can process. A phrase sticks in my mind, one he often repeats: ‘Se fue’—‘It’s gone.’

They can mimic up to seven bird species

Some feathered beauties grant us time for a closer look. The Yellow-bellied Elaenia flits past, followed by the Purple-throated Fruitcrow and the Gilded Barbet. A Black-necked Becard perches on a nearby branch. “They can mimic up to seven bird species,” Christian explains, “including birds of prey like falcons. This deception deters potential predators from their nests and also discourages competitors for nesting sites and food.”

A purple throated fruit crow (Querula purpurata).

The avian spectacle reaches its peak when a jet-black bird with a shimmering purple breast lands nearby. Christian exhales in admiration: “A Purple-breasted Cotinga! They’re known for their elaborate courtship displays.”

Moments later, a Chestnut-eared Aracari, a member of the toucan family, appears.

Its large, curved beak completes its majestic presence.

Its chestnut-coloured facial markings, bright yellow breast with a red band, and iridescent greenish back create a stunning display. Its large, curved beak completes its majestic presence.

A chestnut eared aracari, which belongs to the toucan family.

It’s barely past eight in the morning when we slowly paddle back to the lodge—silent, content, deeply moved. Then, a rustling high above in the canopy: a Squirrel Monkey. The rustling multiplies, surrounding us from all directions.

A group of about thirty monkeys—big, small, young, old—moves gracefully through the treetops. Some communicate with soft ‘chirp-chirp’ or ‘peep-peep’ sounds, likely to signal their positions and keep the group together.

This moment demands undivided attention

I leave my cameras untouched. This moment demands undivided attention. The monkeys leap acrobatically from branch to branch, some appearing to fly over the water channels with astonishing agility. Some nibble on twigs, others edge closer, curiously eyeing us before rejoining their troupe with excited chatter.

Within minutes, they vanish into the foliage. Only the gentle splash of our paddles accompanies us back to the lodge.

A yellow dumped cacique (Cacicus cela) in the jungle near Sacha Lodge.

Visiting the indigenous people of Amazon

As our motorboat cuts through the sluggish waters of the Napo River, naturalist guide Jarol Vaca highlights the uniqueness of our next destination. “The Yasuní National Park, which we are about to enter, harbours over 640 tree and shrub species in just one hectare—more than all the native tree species in the United States and Canada combined.” He pauses meaningfully. “And the insect diversity? Unrivalled. An estimated 100,000 species per hectare.”

“That’s a Hoatzin, also known as the Stinkbird – and for good reason.”

A brightly coloured, pheasant-like bird clumsily lands on an overhanging branch, swarmed by flies. “That’s a Hoatzin,” Jarol whispers, “also known as the Stinkbird—and for good reason.” The bird’s digestive process is so slow that its food ferments, emitting a pungent odour.

“But the most fascinating thing is the chicks,” he continues. “When threatened, they leap into the water and, thanks to special claws on their wings, climb back up the tree trunk—a trait they lose after about a year. Some scientists believe this links them directly to dinosaurs.”

A hoatzin, also known as a Stinky Turkey. Its meat is considered inedible by indigenous people. This is partly due to the very slow digestion process, during which part of the food is fermented and the meat absorbs the resulting odour.

After docking at the riverbank and walking a short distance, the Kichwa community of Providencia comes into view. Tall, steep thatched roofs rest on open wooden structures elevated on stilts. Cinthia Andi and her daughter Smilla greet us with warm smiles.

The community has 150 inhabitants, some living an hour’s walk away. They cultivate their fields near the Napo River, whose nutrient-rich waters act as a natural fertiliser.

Guayusa also helps relieve headaches, soothes the skin, and serves as a natural mosquito repellent

Cinthia offers us Guayusa, a tea-like infusion traditionally sipped from a shallow calabash in the early morning. A fresh leaf contains up to two percent caffeine, while dried leaves can hold as much as seven—the highest known concentration in any plant.

Jarol adds, “At dawn, families gather for this ritual, sharing their dreams and discussing the day’s tasks.” Guayusa also helps relieve headaches, soothes the skin, and serves as a natural mosquito repellent. Scientific studies confirm its antibacterial properties.

Mother Cinthia and daughter Smilla Andi are two members of the very traditional Nueva Providencia Community of around 150 people.

Three turquoise-blue Morpho butterflies dance above the cassava fields. Cinthia leads us to an Achiote bush. She cracks open a spiky red capsule, revealing vibrant red seeds. The pigment, Bixin, has been used for generations as food colouring, body paint, sunscreen, and medicine.

These palm grubs thrive in decaying wood or palm trees

Back at the hut, a local delicacy awaits: skewered, roasted larvae of the Red Palm Weevil. Jarol’s eyes gleam. “These palm grubs thrive in decaying wood or palm trees. They’re rich in protein and have a nutty taste.” After initial hesitation, we try the grilled version. Then, Cinthia presents live specimens. While we politely decline, little Smilla eagerly grabs a grub, takes a bite, and beams at us with unmistakable pride.

A delicacy from the Amazon: roasted palm weevil larvae! These larvae, also known as sago palm weevil (Rhynchophorus ferrugineus), live in rotting wood or in palm trees, are rich in protein and have a nutty flavour.

The Kichwa live by three fundamental rules: never be lazy, never lie, and never steal. Their concept of sumak kawsay, the ‘good life,’ extends far beyond material needs. It describes a deep harmony between people, community, and nature—a principle so significant that it was enshrined in Ecuador’s constitution. Closely tied to this is ayni, a system of mutual giving and receiving that reflects the natural cycle of all life.

We are part of a greater whole, woven into the breathtaking rhythm of nature

The Yasuní National Park covers just 0.15 percent of the Amazon’s total area but is home to a third of all Amazonian reptile, bird, and mammal species. Deep within its forests, the Tagaeri and Taromenane tribes live in voluntary isolation. “Years ago, two men attempted to make contact,” Jarol says in a hushed tone. “They never returned.”

Here, where the boundary between nature and culture blurs, the Kichwa preserve a way of life that reminds me of often-forgotten truths: that we are part of a greater whole, woven into the breathtaking rhythm of nature.

Observation tower, approx. 40 metres high. All components were brought in and assembled by hand.

Where the Amazon keeps its secrets

“The true scholars of the Amazon are its indigenous inhabitants—their knowledge of the forest surpasses any textbook,” wrote naturalist Henry Walter Bates in 1850. His words remain as true today as ever.

In the past, legends of monsters and giants fuelled people’s imaginations

Now, from one of Sacha Lodge’s observation towers, I take one last look at the mighty Napo and the endless green beyond. Where myths of monsters and giants once flourished, visitors today discover an ecosystem of dazzling biodiversity, timeless indigenous wisdom, hypnotic natural sounds, and breathtaking flora and fauna.

View of the Napo River, not far from Sacha Lodge.

Eco-lodges like Sacha Lodge serve as windows into this hidden world, where slowing down and exploration merge seamlessly.

Somewhere in the distance, an unfamiliar bird’s melodic call pierces the evening silence. It feels as if the Amazon itself is bidding farewell, a final reminder that it remains a place of boundless wonder.

Read now:

An island like no other

La Reunion – Like a trip around the world in five days

26 Min.Where else in the world can you splash in the sea in the morning, walk in the rainforest at noon, and marvel at a desert with an active volcano in the afternoon? Reunion offers the most diverse variety of landscapes, vegetation and cultures that I know.

Obituary on the second anniversary of his death

Rüdiger Nehberg – adventurer, madman, hero of humanity

3 Min.You will always remain alive in us. For me, you were and are the hero of my life. You have shown us what a little boy from Bielefeld can achieve in wild capers: A weeklong marathon march with insect meals, crossing the Atlantic in a pedal boat, or simply using an entire jungle as an escape room – always for a great cause, always for others.

Colourful eco-paradise

Costa Rica photo gallery

< 1 Min.Shortly before the 2nd lockdown, I take the opportunity for a short escape to Costa Rica. In almost deserted national parks, an exuberant plant and animal world awaits me. A detailed article on my trip will appear in Terra magazine in April 2021.