Published in:

Germany’s biggest nature travel magazine

12 pages | text & photographs

“Do you see the Komorebi?” asks Dameon Takada, our burly nature guide, just before we enter a restaurant where I’m about to be served cod milt. Later, we marvel at the world’s largest owl, and I fall asleep thinking, “What a day, what a country!”

It’s late afternoon, a light breeze is blowing, and I look at Dameon in confusion. He notices my invisible question mark and points to the nearby forest: “There, the shimmering sunlight filtering through the leaves of the trees – that’s what we call Komorebi.” This poetic word is just the beginning of a series of unique aspects that make Japan captivate visitors like no other country.

A gamer playing on two phones

And yet the day had started very differently. That morning, a Boeing 737 from Tokyo landed at cloud-covered Memanbetsu on Hokkaido. As we descended, I looked out over the snow-covered grey and white landscape and thought: “Well, not very promising”. No wonder, having spent the last three days in Tokyo.

There I was gently jolted awake by a morning earthquake, impressed by a gamer playing on two phones at once with just his index and middle fingers, and fascinated by the long, solemn yet deliberate wedding processions at Meiji Shrine.

I had seen and experienced the answer to how the Japanese manage to keep Greater Tokyo, with its 37 million inhabitants, so clean, orderly and free of stench. But I still couldn’t understand it.

The Fuyiama shortly after dawn and just minutes before landing in Tokyo.

Our guides Dameon and Ayami greet three journalist colleagues and me with a traditional bow and a warm ‘Irasshaimase’, which means ‘welcome’. We board a minibus to take us to Shibetsu.

The temperature is well below freezing and the landscape is covered in pristine white. As we pass snowploughs with massive pipes piling snow into towering walls along the roadside, I realise: this is real winter.

Beneath us, immense geothermal energy bubbles

Dameon grabs the bus microphone: “Hokkaido covers more than 20 percent of Japan’s land area, yet less than five percent of the population lives here. You may not feel it, but we are currently driving over one of the most active tectonic zones on earth.

The fertile volcanic soil on either side of us makes Hokkaido Japan’s ‘breadbasket’. Beneath us, immense geothermal energy bubbles, feeding countless hot springs, fumaroles, and thermal baths with hot water. And above us rise the majestic giants: volcanoes. Six of them are active here in Hokkaido.”

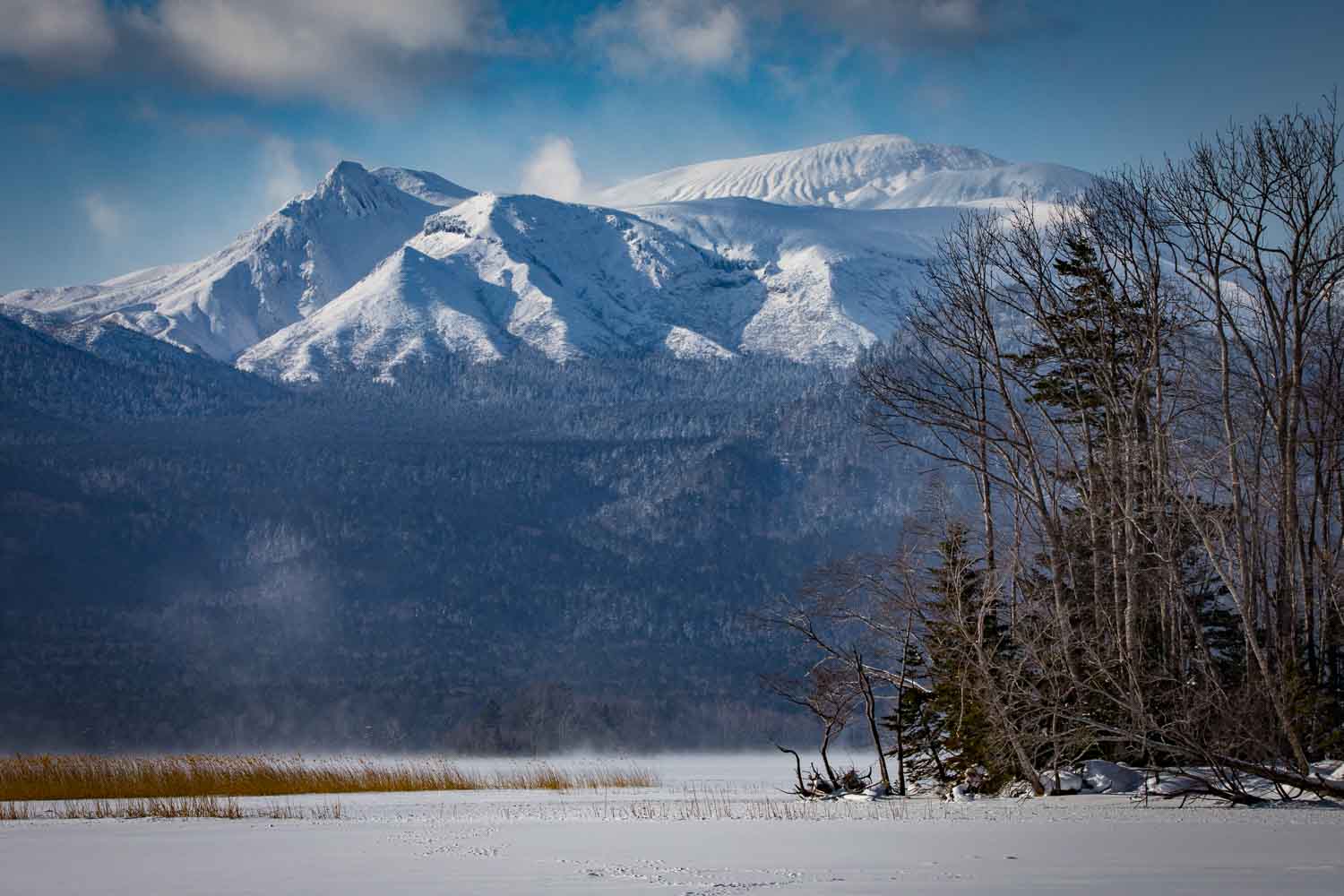

View of the highest point in Shiretoku National Park, one of the most remote regions in Japan: the 1,660 metre high Mount Rausu.

A fox scurries across the road ahead of us. Dameon reacts immediately: “Oh, that’s an Ezo red fox. These animals are endemic to Hokkaido and hunt mainly during the day. In the short winter days, they eat almost anything: insects, beetles, berries, sometimes even birds and carrion. This one searches the snow-covered fields for voles and other small rodents.

When it hears something under the snow, it tenses up, leaps into the air, and crashes down with all four paws onto the roof of a vole’s snow tunnel. When food is scarce, they also feed on dead fish along the coast or discarded gloves by the roadside. They o associate roads with food, which is why many die in traffic accidents.”

Gaming Cup Noodles, caffeinated noodles for impatient gamers

The road is lined with Japanese larches serving as windbreaks. We pass endless snowfields flanked by cherry trees, azalea bushes, and Japanese stone pines. Finally we stop and enter a supermarket. Around ninety per cent of the products are labelled exclusively in Japanese.

Thanks to Ayami, I can identify some of them: Shiroi Koibito, Hokkaido’s famous white chocolate cookies; Ikameshi, a traditional dish of stuffed squid; or Gaming Cup Noodles, caffeinated noodles for impatient gamers.

A seasonal luxury that is only available in winter: ‘Shirako’ – cod seeds in hot broth.

A short time later, we arrive at a restaurant in Shibetsu. As Dameon and I enjoy some delicious sushi at a long counter, I notice excitement and amusement building to my left.

My fellow traveller, Karyn, hands me a small bowl containing a soft, white substance sitting in a dark sauce. She urges me to taste it. Then, she pulls out her phone, presses the record button, and smiles.

“It’s cod sperm!”

I take a bite. The substance melts on my tongue—velvety, slightly grainy, creamy, like a rich cream cheese with a hint of fish. Karyn can’t hold back any longer: “It’s cod sperm!” She’s not entirely wrong; it’s Shirako—cod milt in a hot broth.

Here, it’s considered a delicacy here, only available in winter when the male cod’s reproductive glands are at their most developed. Dameon adds, “Shirako literally means ‘white children’. And you’ve just eaten a real delicacy. We also call it the taste of Hokkaido.”

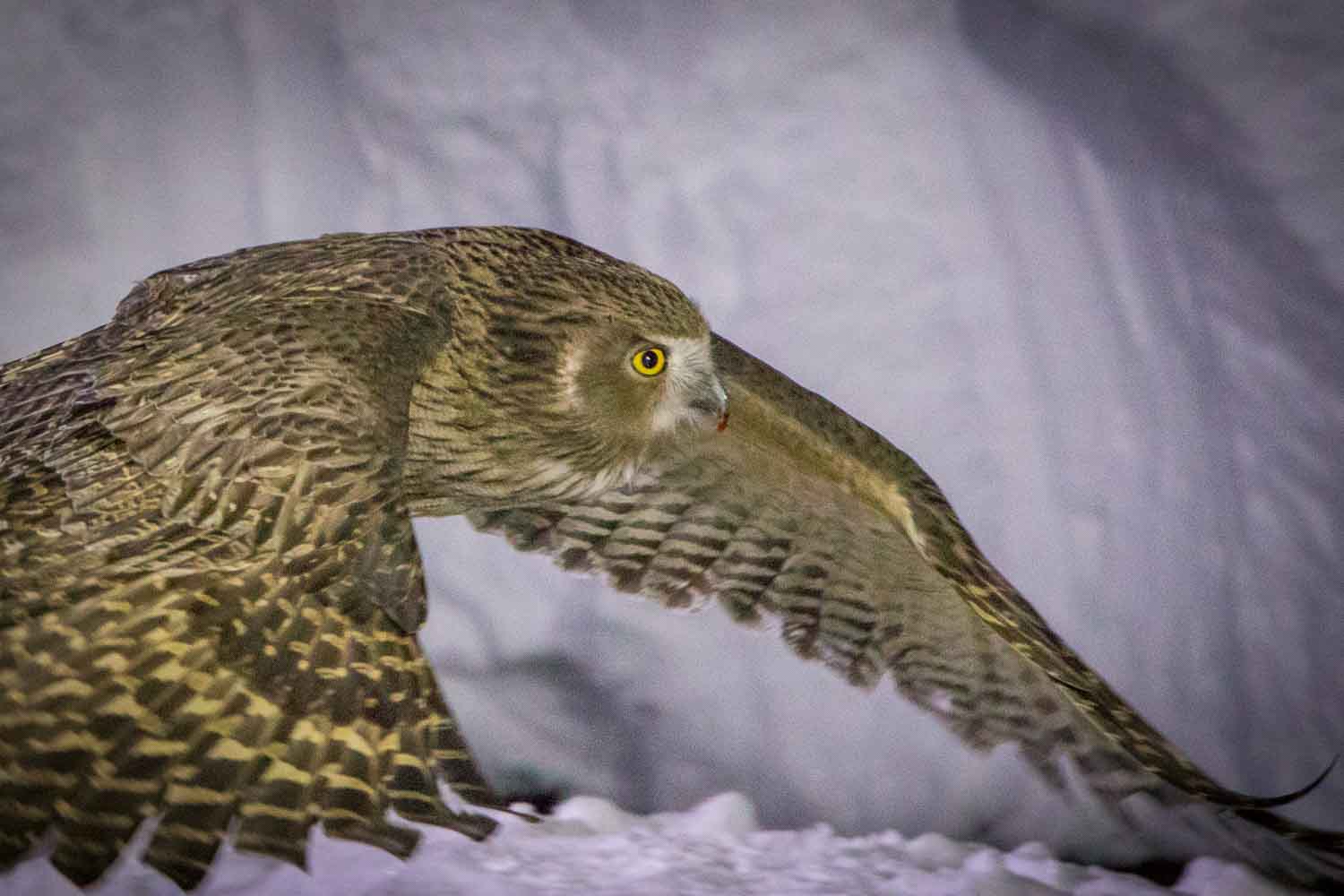

The Blakistons’n fish owl is one of the most endangered species in Japan. It is worshipped by the Ainu as the divine being Kotan-kor Kamuy: protector of the villages.

It’s pitch dark now. And bitterly cold. We’ve been sitting motionless in a wooden hut for almost an hour. Our eyes are fixed on an illuminated spot about 20 metres away, in the hope that a very rare visitor will soon appear: the Blakiston’s fish owl.

And sure enough, an owl silently glides down, probably attracted by the bloody fish carcass, and lands on the snow-covered ground. I watched its every move, unable to take my eyes off this magnificent creature.

The owl turns its head — thanks to its 14 neck vertebrae (we humans only have seven) — an impressive 270 degrees. Then, it dips its beak into its thick, speckled feathers and begins to preen.

The Blakiston’s fish owl is one of the most endangered species in Japan

Its immense size, the quiet grace of its movements, and its piercing yellow eyes — I can easily understand why the Ainu, the indigenous people of Hokkaido, revere this owl as a deity. They call it Kotan-kor Kamuy, the protector of the villages. The owl, which can see in the dark and hunt successfully, embodies for them a mediator between the visible and the invisible world.

Dameon whispers: “The Blakiston’s fish owl is one of the most endangered species in Japan. We estimate that there are only about 130 left. Deforestation has led to a dramatic decline in their numbers.”

The Ainu worship nature and all its creatures as divine manifestations. They believe that every part of nature, from trees to animals to rivers, is inhabited by a spirit. When the owl disappears, the Ainu lose what it symbolises: strength, wisdom, reverence, protection.

The sika deer can also be found on the coastline of the Sea of Okhotsk, where they eat seaweed that has been washed up.

The Ainu worship nature and all its creatures as divine manifestations. They believe that every part of nature, from trees to animals to rivers, is inhabited by a spirit. When the owl disappears, the Ainu lose what it symbolises: strength, wisdom, reverence, protection.

The owl in front of us spreads its mighty wings, which can span up to 190 centimetres, and seconds later, it vanishes into the dark night.

Where do they come from? Where are they going? Who gets off here? And above: Why?

The train station at the end of the world

It’s one of those places where the world seems to end: Kitahama Station. In the middle of nowhere, right on the shore of the Sea of Okhotsk, three or four trains stop here every day. Inevitably, you wonder: Where do they come from? Where are they going? Who gets off here? And above: Why?

The only human presence is the stationmaster, who is busy sculpting a life-sized Pokémon snow figure on the platform.

A bizarre and amusing ritual in an outbuilding of the Kitahama railway station: thousands of visitors immortalised themselves with business cards and small greetings.

Thousands of business cards and handwritten notes cover the walls of the waiting room. This tradition was started by a former stationmaster, who left out a notebook for travellers to record their memories.

It’s also common in Japan to leave your business card in symbolic or remote places as a personal mark or reminder.

They can plunge into the water from a height of 30 metres at speeds of up to 100 kilometres per hour

As I ponder this ritual, I climb the viewing platform next to the station. The view from here of the drifting ice, the vast bay, and the Shiretoko mountain range is breathtaking. In the open areas between the blue-hued ice floes, Japanese cormorants and brown boobys gather.

The latter are among the most skilled hunters in the bird world. They can plunge into the water from a height of 30 metres at speeds of up to 100 kilometres per hour to catch fish at depths of 10 to 30, sometimes up to 50 metres.

White-tailed eagles spend considerable time circling in search of prey.

Why do people feel the need to leave their mark? Perhaps in remote places like this, they are confronted with their own impermanence. In such moments, it seems wise to defy the finite, quickly jotting down a note or a card and pinning it up.

Or perhaps it’s the endless drifting ice that serves as a metaphor for life itself? Ice is unstable, constantly moving and is at the mercy of more powerful forces such as wind and ocean currents.

In Japanese, there’s a term called mono no aware. It describes a deep sensitivity to the transience of things, a gentle sadness. And there’s no better place to experience this feeling than Kitahama.

‘King of the northern sky

Hokkaido’s sky hunter

One of the world’s most majestic birds of prey, the Steller’s sea eagle is reverently called the ‘King of the northern sky’ in Japan. Compared to the equally impressive white-tailed eagles, these giants are easily recognised by their massive yellow beak and distinctive white shoulder feathers.

White-tailed eagles, on the other hand, have brown plumage and are physically smaller. Both species of eagle spend a lot of time soaring in wide circles in search of prey. Along ice-free coasts and rivers, they hunt fish, ducks, and gulls before returning north.

White-tailed eagles that have bred in eastern Russia migrate to Hokkaido for the winter. There they hunt for fish, ducks and gulls on ice-free stretches of coastline and rivers.

Just outside the port town of Shiretoko Rausu, on the open sea, we watch about seventy eagles on their spectacular hunt for fish. Dameon explains: “There are only about 5,000 Steller’s sea eagles worldwide, and 2,000 of them come to Hokkaido every winter, with 500 arriving in this region.

They originate from Sakhalin, the Ussuri region, or Kamchatka. Some travel thousands of kilometres to get here. These long journeys seem to keep them fit, and some live to be over 40 years old.”

Before our eyes, the fascinating sequence repeats itself countless times: gliding, diving, catching, soaring. It never gets boring. The strength, elegance, and precision of these magnificent birds is overwhelming.

Fumaroles bubble hot mud from the depths of the earth

Hidden wonders under the ice

“Be careful and follow me without going too far left or right. I don’t want you to fall into a Yutubo,” warns Dameon before we step onto the frozen Lake Akan in our snowshoes. “Yutubos are patches of thin ice that are hard to see. The steam from the hot springs below has melted the ice.”

At Lake Akan, it is easy to realise that you are in a geothermally active area: In the main town of Akan-ko Onsen, steam rises from almost every manhole cover, fumaroles bubble hot mud from the depths of the earth, and the air in the forest carries the scent of sulphur.

The lake itself is a crater lake nestled between two active volcanoes. It is home to twelve fish species and 259 freshwater algae, including a real oddity: Marimo.

View over Lake Akan to the 1,499 metre high active volcano Mount Meakan.

Marimo colonies are among the strangest plant communities on earth. Only in Lake Akan do they grow into balls over 15 to 30 cm in diameter, making them the largest algae balls in the world.

Their formation is due to a complex interplay of sunlight, wind-driven currents, geothermal warmth, sedimentation, and the nutrient content and quality of the water. Upon closer inspection, the balls consist of fine, thread-like green algae, which tangle into balls due to the lake’s special conditions.

During the day, the balls float to the surface, and at night, they sink to the bottom. This rise and fall is controlled by photosynthesis. Oxygen forms in the algae network as tiny bubbles during the day, and once enough bubbles are present, the ball rises. As the light fades in the evening, the bubbles shrink and sink to the bottom of the lake.

In Japan, Marimo are revered as a ‘national treasure.’ It is said that if you take care of a Marimo at home, your wish will come true.

The wind is relentless

Dameon steps onto the frozen lake, and we obediently follow in his tracks. The wind is relentless, whipping snowflakes into our faces, piling them thicker and thicker on our clothes. Winter at last, I think to myself. Half an hour later, we leave the lake and head for lunch.

Delicious beef tataki arrives on the table, a tender texture of beef combined with fresh cabbage, radishes, peppers, onions and intense sauce flavours. “Eat a lot,” Ayami recommends, “this afternoon we’re going into the forest for a few hours.”

Keryn marvels at the frost crack on a tree. These can occur when the temperature suddenly drops to around -25° Celsius.

A symphony of the silent forest

A black and white kingfisher glides by. The wind rustles through the treetops like a gentle sea breeze. The only sound breaking the silence is the crunch of our snowshoes, saving us from sinking into the one metre deep snow.

The forest around Lake Akan is a place of peace, far from any civilisation noise. “Look, there are tracks of squirrels, deer, and foxes. Perhaps from this morning,” Dameon observes.

About a hundred metres ahead, sika deer cross our path, stop and stare. “Ah yes,” Dameon sighs, “the deer may look cute, but their numbers have increased dramatically. Now, with the snow so deep, they feed more on tree bark, saplings, and young trees.

They also graze along coasts and on farmland, causing damage there. The black crowberry and other plant species have almost been wiped out. To control the population, they are allowed to be hunted from October to March.”

That’s a frost crack. Some are up to four metres long

I point to a tree with a long vertical crack. Dameon explains: “That’s a frost crack. Some are up to four metres long. They form when the temperature suddenly drops to around minus 20 degrees Celsius.

The water in the tree trunk freezes quickly into ice and expands. This can cause the wood to split suddenly, often with a crack as loud as a gunshot.”

Strong winds make visibility difficult during our snowshoe hike on frozen Lake Akan.

A chopping sound makes us stop. Dameon chuckles and says, “That’s just a black woodpecker. There are six species of woodpecker here in the forest and this is the largest. They grow up to fifty centimetres long with a wingspan of seventy centimetres. You can easily recognise them by their pitch-black bodies and bright red heads.”

For the Ainu, this bird is also a deity. They believe the woodpecker has a protective role, warning of bears with loud pecking and special calls. The woodpecker has also shown the Ainu that wood can be shaped.

With its beak, it carves not only round but also rectangular, boat-shaped holes in tree trunks. In the Ainu language, the black woodpecker is called Ciptacikap-Kamuy, the ‘god who carves boats.’

That’s a Japanese katsura tree

Now, a huge fallen tree trunk catches my eye. Ayami explains: “That’s a Japanese katsura tree. In late autumn, from the end of September, its heart-shaped leaves release a scent reminiscent of caramel, candy floss, or freshly baked cake. This is due to the maltol that is released when the leaves change colour and fall.”

During a hike on snowshoes, without which we would have sunk about a metre into the snow, we discover this wonderful place, which invites us to linger and marvel at the wonderfully peaceful nature.

High above us, a small bird flits from branch to branch. I notice excited reactions of our Japanese companions. I later learned that it was a Hokkaido long-tailed tit.

These small, fluffy birds are beloved in Japanese pop culture for their snow-white plumage, round shape, small eyes, and short beak. They are popular subjects for plush toys, key rings, charms, and in confectionery designs.

At the end of the day, after so many impressions, information, and fresh air, I long for some peace in a quiet corner of a café. As I reflect on the past few days, I come across a concept in a book that sums it up in a Japanese way: Wabi-sabi. It means finding beauty in imperfection, transience, and simplicity.

Read now:

Colourful eco-paradise

Costa Rica photo gallery

< 1 Min.Shortly before the 2nd lockdown, I take the opportunity for a short escape to Costa Rica. In almost deserted national parks, an exuberant plant and animal world awaits me. A detailed article on my trip will appear in Terra magazine in April 2021.