Published in:

Germany’s biggest nature travel magazine

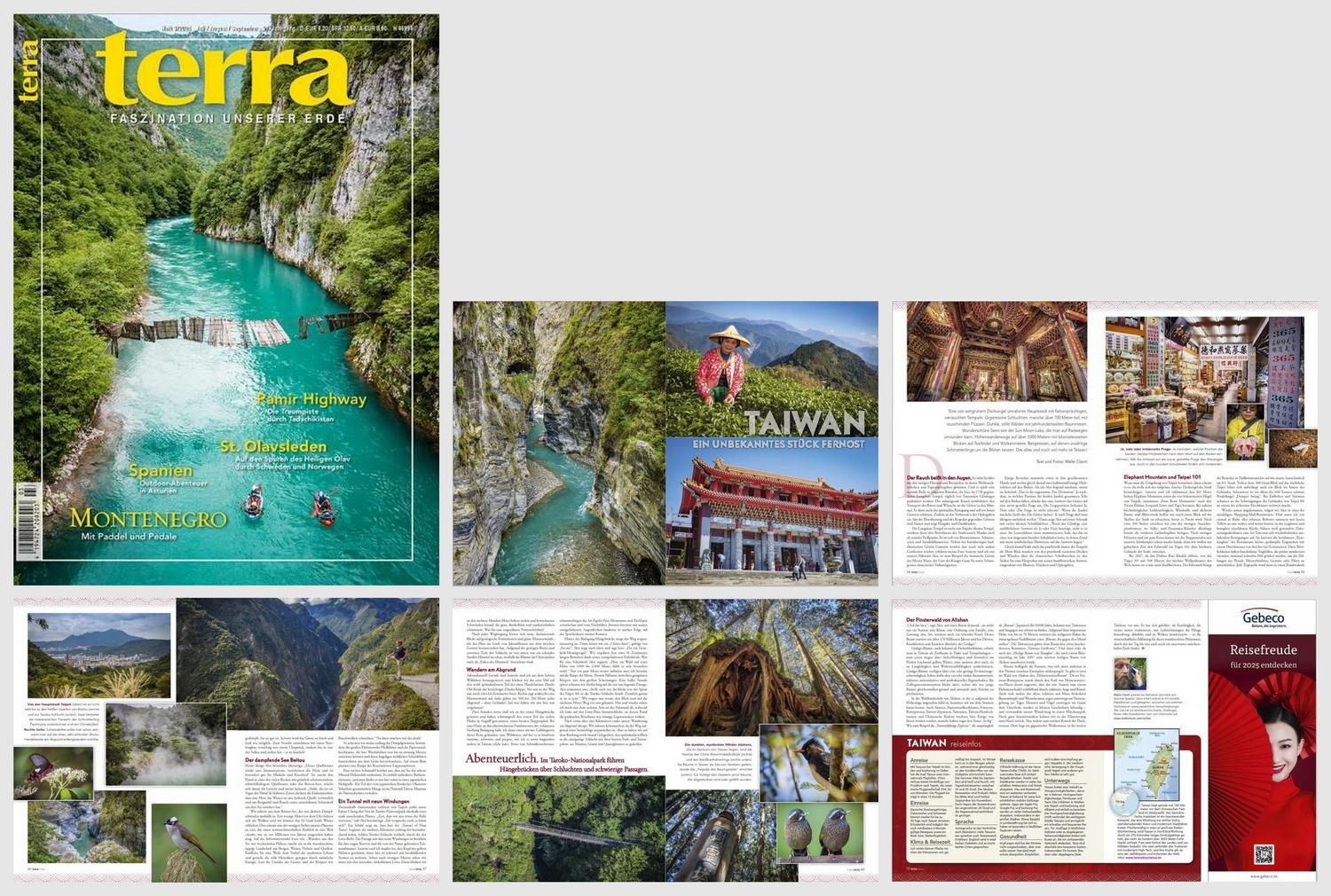

10 pages | text & photographs

Longshan Temple

Smoke bites into my eyes. It drifts over from the huge pans and kilns in which incense sticks and paper offerings glow. And it plays a central role in religious rituals, which are practised daily by thousands of believers here in the Longshan Temple, founded in 1738. The rising smoke symbolises the transport of requests and wishes to the gods to heaven. It is also used for spiritual purification and is said to protect against evil spirits. In addition, burning the offerings is an act of reverence and respect towards the gods and ancestors and shows devotion and gratitude.

Longshan Temple is not only Taipei’s oldest temple, but also serves as a social meeting place for the residents of the Manka neighbourhood. The temple is full of bronze statues, carvings and stone sculptures. In addition to the merciful Buddhist goddess Guanyin, many other deities are worshipped here, such as the Taoist goddess of the sea Mazu, the god of war Guan Yu and guardian spirits of Chinese folk religions.

When night fell, Guanyin began to radiate a dazzling light

Our guide Alex recounts the legend of the temple’s origins: “It is said that Chinese immigrants from the city of Jinjiang in Fujian province carried a Guanyin statue or amluet with them so that it would offer them protection on their journey and ensure a good life in their new homeland. When they arrived here and night fell, Guanyin began to radiate a dazzling light. The people quickly discovered that Guanyin was also able to fulfil wishes. And so, within two years, they had built a temple on this spot.”

Then I watch as visitors mumble something into their closed hands and immediately afterwards drop two crescent-shaped pieces of wood on the floor.

One of the main altars of the Longshan Temple in Taipei.

Alex smiles and says: “This is the so-called ‘poe divination’. Depending on the position in which the two parts, called jiaobei, fall to the ground, this expresses an answer from the gods to a previously asked question. As a rule, a yes-no question is asked. The lying position of the jiaobei then answers with yes, no or ‘The question is not relevant’. If the pieces wobble, it means ‘the gods are laughing’. Depending on the question, you can throw several times.”

Yes, hope dies last here too, I think. While I’m still thinking this through, Alex continues, pointing to a cupboard with lots of little drawers: “But if a believer needs a more sophisticated answer than ‘yes’ or ‘no’, he draws a numbered stick in a kind of lottery. This in turn directs them to one of a total of 100 drawers. Each drawer contains a special slip of paper with further, usually symbolic, clues to the answer.”

Flowers, fruit and offerings decorate the altar

Immediately afterwards, I am distracted by one of the temple’s magnificent altars. My gaze wanders over the beautiful and lavishly decorated ceilings and walls, adorned with elaborate carvings and golden ornaments. A main altar with many Buddhist statues is enthroned in the centre, including a central one depicting the goddess Guanyin. Flowers, fruit and offerings decorate the altar. Traditional Chinese characters adorn the pillars. I marvel open-mouthed at the ornate, symmetrical ceiling patterns.

Elephant Mountain offers a comprehensive and popular view of the city, which is illuminated in the early evening.

Elephant Mountain and Taipei 101

Looking at Taipei and its surroundings, it seems as if the deep green, humid jungle around it is trying to take over the city. Annette and I climb a foothill, the 183 metre high Elephant Mountain in the city area, one of Taipei’s four significant hills, collectively named ‘Four Beast Mountains’ after the elephant, leopard, lion and tiger.

With almost the highest possible humidity, an absent breeze and dense trees and foliage, we hope to catch a glimpse of Taipei before the night swallows the sun. After about 350 steps, we reach one of the few viewing platforms. Selfie and panorama artists are already occupying the front railings with a view of the skyline.

After a few minutes and a few photos, we hurry back down the headlamp-lit steps as we want to catch the lift to ‘Taipei 101’, the tallest building in the city, at the time we have booked.

In the event of earthquakes and storms, this reduces the building’s vibrations

Until 2007, before it was replaced by Dubai’s Burj Khalifa, Taipei 101 was the tallest skyscraper in the world at 508 metres and is still the fifth tallest today. The lift transports visitors to the inner observation deck on the 89th floor in no time at all. In addition to the 360-degree view of Taipei at night, it is definitely worth taking a look inside the building. The 660-tonne “Damper Swing” pendulum sphere is well worth seeing. In the event of earthquakes and storms, this reduces the building’s vibrations, making Taipei 101 one of the safest skyscrapers in the world.

You can watch the 18 chefs and kitchen assistants at Din Tai Fung Restaurant as they prepare their famous xiaolongbaos, stuffed dumplings.

Din Tai Fung 101

Once back downstairs, we follow Alex into one of the countless shopping mall restaurants that seem interchangeable from the outside. Once inside, at the last free table, I first have to take everything in: There are robots buzzing past us with empty plates, further back, in the fully glazed and completely visible kitchen, a theatre of preparation acrobats, all clad in white, who have come together in a strange ritual, half dance, half repetitive, escalating movements, to create the Din Tai Fung restaurant’s famous ‘xiaolongbao’: small, steamed dumplings with a diameter of 3 to 4 centimetres.

There are robots buzzing past us with empty plates

These delicacies have wafer-thin pastry shells, precisely folded at least fourteen, maximum eighteen times to enclose the delicate fillings. The trick is to make the pastry so thin that it is tender, but strong enough to hold the hot broth. The latter is created by adding chilled meat gelatine to the filling, which melts during cooking.

Flavoured stock then takes up its charge: Beef, pork or lamb, seafood, red bean paste made from adzuki beans or vegetables such as pak choi, kailan, Chinese cabbage, jiucai, mung bean sprouts, bamboo shoots or shiitake mushrooms. Each dumpling is then placed in a bamboo basket and steamed until cooked. The whole thing is served as fresh and hot as possible.

To eat, we carefully remove a xiaolongbao with a chopstick, dip it in ginger julienne, soya sauce or vinegar, bite a small hole in it and then sip the broth before savouring the inside: spicy pickled cucumber, steamed prawns, pork shao mai, fried cabbage and water spinach and, for dessert, red bean xiaolongbao and fried sweet potato leaves.

Annette looks at the 92-degree Celsius hot water of the Beitou hot spring in Taipei.

The steaming Lake Beitou

Alex sounds particularly convinced today: “This spring water strengthens your immune system, beautifies your skin and is particularly good for your muscles and bones!” She dips her hand into one of the many pools of cooled, greenish shimmering, sulphurous spring water near the Beitou. Alex then adds, washing her face and laughing: “Ahhh, that’s a blessing from nature! Back then, the locals thought that ghosts and demons haunted the area. And that a witch protects the area with the help of her magical powers. She is said to have turned mountain mist and smoke into an invisible protective wall and the water into a healing spring.”

We see the 92-degree hot pool

We approach Lake Beitou, which is shrouded in thick clouds of steam. Only a few metres from its shore do the clouds clear and we can see the 92-degree hot pool.” This seems to be one of the few places on our planet that allows a time machine-like insight into a pre-world as it may have looked millions of years ago.

We study the instructions on an information board: “Walk around the lake with changing heights, immerse yourself in the beautiful lush landscape of mountains, water, mists and springs. Escape the hustle and bustle of modern life for a while and enjoy the quiet serenity, blessed by natural energy. Let the restlessness of the mind and body melt away like clouds of smoke.” Well, let’s do that then!

‘I see you!’ seems this caterpillar of the Theretra pallicosta butterfly to be saying.

We continue to walk along the steaming water, admiring the large elephant ear dart leaves and the paper mulberry trees, which can reach heights of up to 20 metres here and whose spherical female false flowers glow fire engine red from the greenery. A caterpillar of the rose myrtle moth rests on a leaf.

Hokutolite is a rare mineral that contains radioactive radium elements

Another display board informs visitors that the rare mineral hokutolite is found in the lake. It is the only mineral among the more than 4,000 naturally occurring minerals in the world that is named after a Taiwanese town, Hokuto being the Japanese name for Beitou. Hokutolite is a rare mineral that contains radioactive radium elements and is only found here and in a Japanese healing spring. Part of the quantity collected by the Japanese explorer Okamoto Yohachiro is kept in the National Taiwan Museum as a national treasure.

Starting point of our hike through the Taroko Gorge.

A tunnel with nine turns

Two and a half hours’ drive from Taipei, Cheng parks the van above a rushing river. “Time to stretch our legs a bit,” Alex calls out cheerfully, “it’s worth it, I promise.” A sign tells me that the ‘Tunnel of Nine Turns’ starts here and runs for a few kilometres along an impressively deep gorge.

The winding course of the Liwu River has created a wild gorge with many bends. And the passage with the nine bends is known for its tight curves and the complex rock face patterns formed by nature. Well then.

What an untamed natural beauty!

Annette and I trudge off, our heads protected by yellow helmets, because we can always expect falling rocks here. After just a few metres, we can see the turquoise-blue Liwu River hissing below us. Then we stretch our heads high over steep, overgrown rock faces several hundred metres high, shimmering grey, dark blue and sandstone-coloured. What an untamed natural beauty!

After every bend in the path, there are new, fascinating views of geological formations and smooth marble walls that the Liwu River has eroded out of soft rock over millions of years. Due to its narrow width and enormous depth, the sky can only be seen to a very limited extent from below, which is why the gorge is also known in Chinese as the ‘thread of the sky’.

The respect that is demanded of you on this route, which is not free from vertigo, is also breathtaking: Annette on the old, very narrow Zhuilu trading route, from which you can look down many hundreds of metres onto the Liwu River.

Hiking on the precipice

Adrenaline rush! Annette and I have just stepped out of the sparse forest and now we have our first glimpse of what is probably the most spectacular part of the old Zhuilu trade route: the infamous Zhuilu Cliff. In front of us, the path narrows to a width of around 60 cm. On the right is a vertically rising marble wall, on the left a precipitous drop, between 500 and 700 metres deep, without railings! What have we let ourselves in for here?

Two hours earlier, we started at the first suspension bridge and took the first part of the steep path, a wide flight of steps, with great vigour.

There, I found one of my favourite places in Taiwan

We paused at the overgrown foundations of the former settlement of Badagang, which served as a base for the Japanese during the colonial era. There, in a wild meadow, I found one of my favourite places in Taiwan. It was buzzing, whirring and chirping in a biodiverse way that I hadn’t experienced anywhere else in Taiwan. Photos of butterflies of the species Papilio Paris Hermosanus, the common rose (Pachliopta aristolochiae) and those of the moth Junonia lemonias with its numerous orange-coloured eyespots now landed on my camera’s memory card.

Behind the Badagang suspension bridge, the path climbs in serpentines. Then we hear a “Chirit-chirit”, followed by “Sri-sisi”. Alex points upwards and says quietly: “There, a grey-throated minivet.” We spot the 18 cm long bird thanks to its orange plumage. What a beauty! Alex adds: “Here, in the forest at an altitude of 1,000 to 2,000 metres, it feels at home. This is its natural habitat.”

Probably the butterfly Papilio Paris Hermosanus.

Half an hour later, we look in awe at the passage ahead of us. Alex encourages us: “Imagine looking down on the Taroko Gorge from the top of Taipei 101. That’s pretty much what it’s like now.” We venture forward, our gaze fixed on the two metres of path in front of us. Every now and then I lean on the rock face with my right arm as I look down to the left at the Liwu River, at the edge of which the parked coaches look like tiny Lego bricks.

I wonder why the Truku, the former inhabitants of this region, decided in favour of this inaccessible new home when they settled here between 1680 and 1740, coming from the Nantou region and settling in 79 villages along the Taroko Gorge.

We reach the end after just over three kilometres

Alex tells me that the path was originally part of a longer mountain pass and that you can find other remains of settlements and market posts along this ten kilometre stretch.

We reach the end after just over three kilometres. We have to turn back as part of the following path is impassable due to falling rocks. But on the way back, we have another opportunity to catch spectacular views of the unique gorge with its wide range of colours and textures of marble, granite and quartz mica.

Somewhere in the dark, mystical forests of Alishan.

The Dark Forest of Alishan

“And this here,” says Alex, pointing to a tree, “is not only a trunk, a class, an order, a family, a genus, a species, but also a living fossil. It has existed for over 270 million years and survived droughts, diseases and ice ages: The ginkgo tree.”

Ginkgo trees, also known as fan-leaf trees, are valued in Taiwan as ornamental trees in parks and temples – because of their characteristic fan-shaped leaves, which are bright yellow, especially in autumn. They symbolise longevity and resilience. Ginkgo extracts are used in traditional Chinese medicine and are valued by the Taiwanese for their ability to improve circulation and memory.

Some of them are revered, some even have ‘sacred’ status

In the rich forest landscape of Alishan, where it is pleasantly cool due to the altitude, we are hardly able to stop marvelling. Acacias, paper mulberry trees, Formosa red cypresses, Taiwan cypresses, Taiwanias, Taiwan hemlocks and Chinese pines also grow skywards here. Some of them are revered, some even have ‘sacred’ status. For example, the ‘thousand-year-old cypress’, which was originally known as ‘Banzai’, Japanese for 10,000 years. You can linger in the Bo’ai pavilion dedicated to the tree and recite inscriptions from a poem.

Many Taiwanese believe that trees are the home of spirits. The ‘Pagoda of the Tree Spirit’ honours the spirits of trees that have died or been felled.

Taiwan, on the other hand, are difficult to find. Due to their imposing stature, the indigenous Rukai called them ‘trees that bump into the moon’. The Taiwanese gave the tree the somewhat more modest nickname ‘Taiwan’s grandfather’.

Tigers, monsters and birds now emerge from the undergrowth in our minds

And then there is the ‘Sacred Tree of Xianglin’. After a lightning strike search and the felling of its predecessor in 2007, it was officially chosen as the second sacred tree of Alishan. An information board continues: “The tree […] continues to accompany visitors on their journey through time, witnessing every stage of people’s lives.”

View of the sea of clouds from Alishan.

Trees inspire the imagination, even when it comes to naming individual specimens. The ‘elephant trunk tree’, originally a Formosa red cypress, has been damaged by hymenomycete fungi to such an extent that the dead trunk now bears a striking resemblance to an elephant’s skull, including its eye and trunk.

Many other old tree stumps and root systems, some covered in moss, can also spark the imagination: Tigers, monsters and birds now emerge from the undergrowth in our minds, coming to life in little stories – and ennobling our hike into a fairytale adventure. Still drunk on fantasy, we return to the hotel at dusk.

Alex urges us to visit the roof terrace as soon as possible. There, a gigantic ‘sea of clouds’ lies before us in the wide valley plain. This is because the moisture that evaporates further down trickles up the slopes with air currents, cools down and condenses into clouds. And so our little fairytale story comes to an unexpected and very real end.

Read now:

Filming in Berlin

My family on TV

2 Min.Yesterday a TV crew from WDR interviewed my family about our world travels – and what we learned from them. The feature will be broadcast in the series ‘Familie ist …?’ on 9 June 2022 at 10:15 p.m. on WDR and is already available in the ARD media library and on YouTube.

A journey with the Royal Canadian Geographic Society

Arctic – Ship expedition from Canada to Greenland

20 Min.Aboard the research vessel ‘Resolute’, I lent a hand as a temporary scientist and helped collect data. The expedition took us through the Canadian Arctic to the breathtaking fjords of Greenland.

A voyage of discovery in the Amazon

Brasil photo gallery

< 1 Min.Expedition into the depths of the Amazon region with all its inhabitants. I was in the middle of it with a small group and couldn’t get out of my amazement.